Deborah Copaken is a New York Times bestselling author of seven books, including Shutterbabe, The Red Book, Between Here and April, and Ladyparts. A contributing writer at The Atlantic, she has also written for Emily in Paris. Her work as a photojournalist and Emmy Award–winning news producer has appeared in Time, Newsweek, and The New York Times. Her essays have been published in The New Yorker, The Guardian, The Financial Times, and The Wall Street Journal. Her New York Times column “When Cupid Is a Prying Journalist” inspired an episode of the Modern Love series. She currently leads the Webby Award-winning Substack newsletter Ladyparts as its founder, writer, and publisher.

Could you tell us about how your career began?

When I got to college, I wanted to be an English major, but at the time, deconstructionism and Jacques Derrida were huge, and I didn’t like only reading for subtext. I wanted to take the text at face value. I wanted to create art and write, not constantly think about literature as an entity. Harvard had one creative writing class I applied to, and I didn’t get in. So I was like, “Oh, well, I guess I’m not a good writer.” And then I got a C+on my first freshman expos paper. I was like, “Oh, I guess I’m definitely not a good writer. Well, what can I do here at this college?”

There’s a department at Harvard called Visual and Environmental Studies (VES). So I said to myself, “Well, let me just take a class in VES and see what’s what.” And I loved it. I made a documentary about the Boston Ballet, and then I started making fiction films. Then I realized that if I wanted to switch my major to VES, I had to take a class in a different art medium. So I looked through the course catalog, and I saw that there was a photography class. I’ve always felt like a little bit of a loner. And with filmmaking, I had to be collaborative. I had to find people to do the sound and the lighting, I had to have actors, and I had to be organized. I’m not organized. It did not speak to the parts of me that were creative. I realized that I preferred doing creative work alone. So I decided to dive headfirst into photography. So, I took an introduction to photography class, and I fell massively in love at first sight.

Christopher James, my photography professor at the time, said, “I want you to do a photo essay that scares you.” So I decided to go to a strip joint. I didn’t want to cover the men in the front of the house because not only did I think that would be too dangerous and weird, but I also just wanted to bond with the strippers backstage, behind the scenes. And so that’s what I did. I ended up doing this year-long photo project on what was then called the Pussycat Lounge.

Gilles Peress, who is a photographer at Magnum Photos, took an interest in my work, and he said, “Do you want to come work at Magnum this summer? There’s an unpaid internship.” So I worked as a waiter at night and at Magnum during the day. While at Magnum, I got to see everything. My job was to take the photographs back from the magazines, record their return, and then refile them. That was my job, all day long. I got to see history every day in the palm of my hand. Beautifully rendered history, shot by photographers whose work was in museums. I just thought, “Okay, this is it. That’s what I want to do. I want to be a war photographer. I want to experience that.”

As both an artist and writer, how did you transition from photography to journalism?

I think that we should go back to the beginning and say that I never planned to be multifaceted. Each industry I entered subsequently died, so I had to adapt. I’m not saying that photojournalism is dead. I am saying I, as someone without a trust fund, realized I was not going to be able to support myself anymore as a photojournalist. When I started, you used to be able to get $10,000 to publish a few photos in a magazine. Then, suddenly, a few years later, just as digital cameras came on the scene, and the magazine industry started to lose advertising dollars, it was down to $400. It was an unsustainable career.

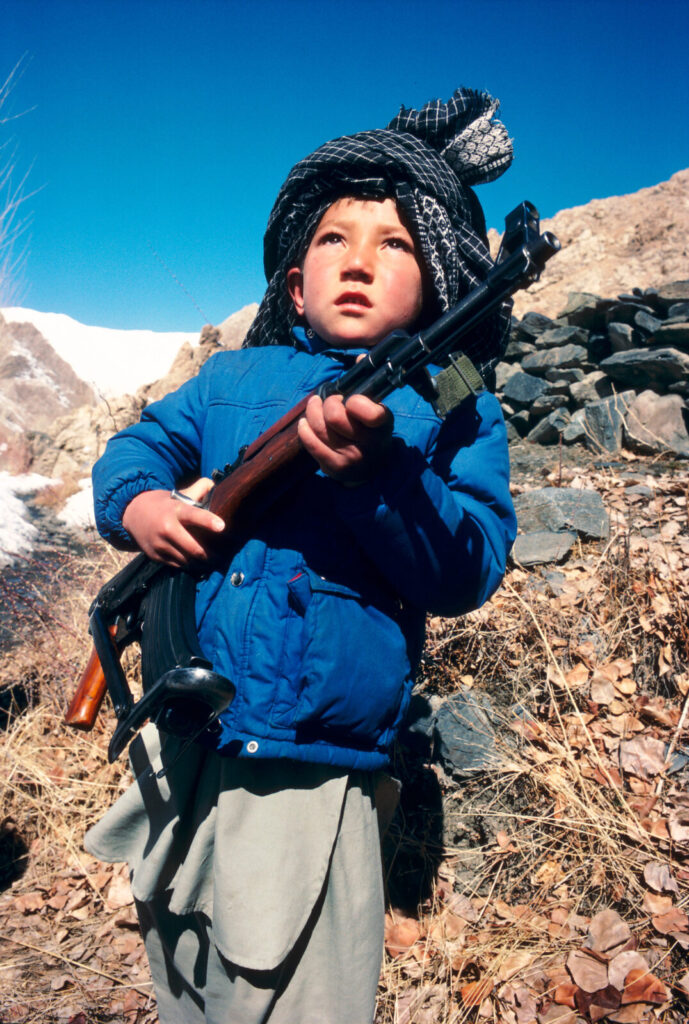

I lived in Paris for four years to have easier access to the world’s hotspots at the time. I covered Afghanistan in 1989. I covered Israel during the First Intifada in 1988 and 1989. I covered the Romanian Revolution, and then I moved to Moscow and covered the Soviet Union during the coup; anyway, a lot of stories between 1988 and 1992. Then, I decided to move back to the States. I worked at ABC News for two years, at a magazine show called “Day One,” and then I got a job at Dateline NBC. So, for six years, I was working in a very highly corporate structure with 401Ks, health insurance, and all the benefits, which I needed if I wanted to give birth and have kids. In the beginning, I felt that I was making some sort of a difference, because I was doing stories on Chinese dissidents sneaking back into China. I was doing stories on Ibogaine, which was being used to treat drug addiction. I was doing stories, particularly at ABC, that I felt had a greater purpose, and then suddenly that industry, too, had to adapt to the juggernaut of the internet and the attention economy, which forced it to become much more sensationalist.

When did you first realize that your own art could make a political statement?

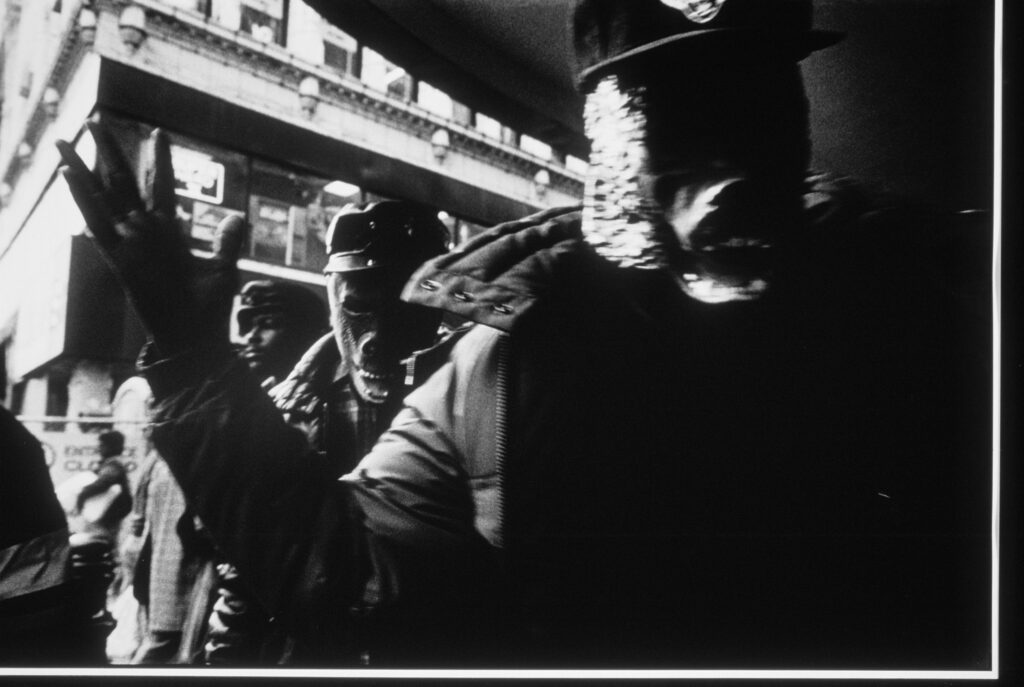

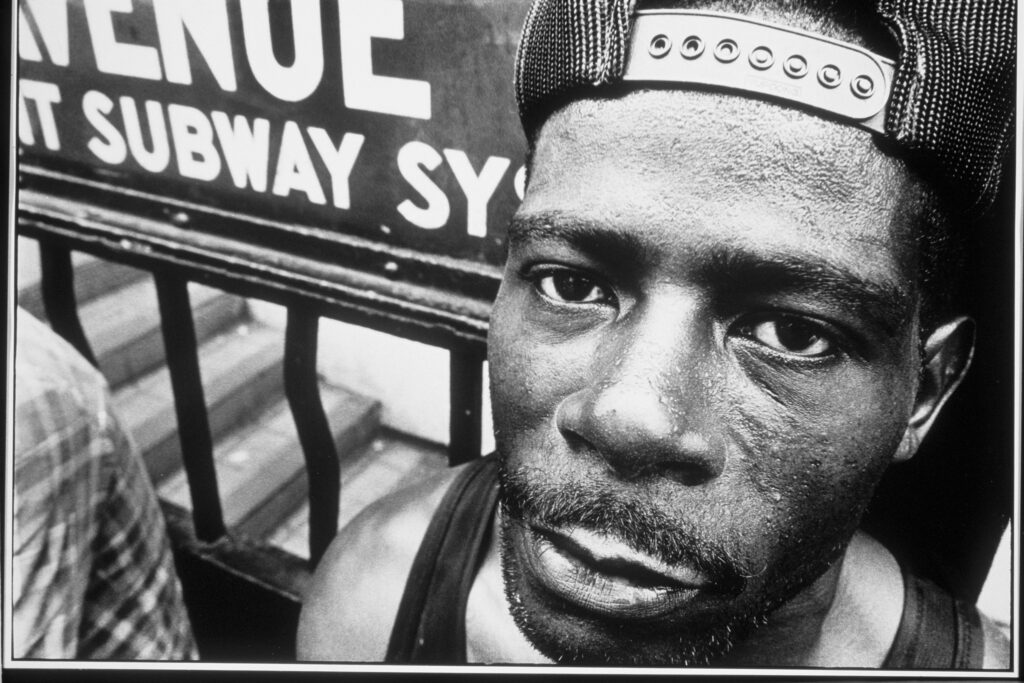

There was a moment in college. It was the crack era, and there was a lot more crime in the streets. I had been a victim of several violent crimes. A man kicked me unconscious in the middle of Harvard Square, I was robbed at gunpoint coming out of a Chinese restaurant, and then later in a New York City taxi. I was working on a Shakespeare paper in my dorm room, and an unhoused man broke in and threatened to rape me. I was date-raped on another occasion. So, for my senior thesis, I wanted men to understand what it feels like to be a woman in the world. To be preyed upon, constantly. So I deliberately chose to go out into areas that were specifically thought to be dangerous for women—red light districts, etc.—and if a man came up to me in those areas and said, “Hey baby, want to get it on?” instead of simply passing him by and sucking it up, I would stop, turn around, and say, “Hey, no, but I have this camera, and I would love to take your photograph.”

This did two things. One, it changed the dynamic of that predator-prey relationship—suddenly, I was the predator, and they were the prey. Also, I shot them with a 28 millimeter lens super close to their faces, so that their faces were kind of distorted and bizarre-looking. Two, the impression this gave when I had them up on the wall, a man walking into that exhibit would think, “Oh, this is what it feels like to be preyed on lasciviously. Here’s what it’s like to be a woman in the world.”

This was the first time that I realized you can use art to make political statements that don’t hit you over the head, but are more subtle. I called it Shooting Back. And it was with Shooting Back that I was able to get a foot in the door in Paris when I moved there because that work made me a finalist in the W. Eugene Smith Award, and then it was published in PHOTO and Photo Magazine, which was a big deal at the time. That thesis kick-started my career.

What inspired you to write your first book?

I had two kids while working at Dateline: my son in 1995 and my daughter in 1997. I went back to work each time after short maternity leaves that were unpaid, which I still think was insane. My son just turned 30, and I cannot believe that after screaming about this, both publicly and privately, for 30 years, we still don’t have paid maternity leave in the U.S. I went into debt to breastfeed my children!

I was the primary wage earner in my marriage. I was not even back to work yet after my second child, but then Princess Diana died, and I was taken off leave and sent back to Paris to cover the fiasco because I knew all those photographers in Paris who’d been arrested, and our executive producer knew that. In the rush to get to the airport from a family vacation in Delaware, I didn’t have time to retrieve my breast pump back home. I was still breastfeeding full-time, hadn’t weaned my daughter off it at all, and the pain of that buildup in Paris was excruciating. That’s when I had this moment of “I don’t know if I can do this job anymore. It’s not what I got into journalism to do.” I didn’t feel that I was creating art with a capital A. I was chasing stories the same way the paparazzi were chasing Diana: as a means to garner money, advertising dollars. It wasn’t working for my moral compass. It also wasn’t working with motherhood.

So I took a risk. I took a leave of absence from NBC and decided to write a few chapters of Shutterbabe to see if I could sell it and start a new career. I sold those chapters and a proposal for the rest of the book for $175,000, which was twice my Dateline salary at the time. I suddenly bought myself two years of working on that book and being my own boss. I really enjoyed writing my first book, but again, I had this nagging voice in the back of my head from my college days of getting that C+ on a paper and of not getting into a creative writing class. Am I a real writer? Can I do this? Suddenly, I was just learning on the job; I had a contract to fulfill and a book that I was passionate about writing.

As someone who has navigated journalism, television, publishing, and memoir, how do you handle the tension between personal truth and public reception, especially as a woman telling politically or emotionally charged stories?

When Shutterbabe came out, it was a far more sexist era, and the reception to that book was insanely misogynistic. One journalist from a national magazine asked me, “Are you worried that your frankness is going to get you labeled a slut?” That would not fly in 2025, but back then, it not only flew, she put her question and my answer into her article! I know that kind of sexism also harmed book sales. That’s the real crime of sexism in literary criticism, right? It takes away my ability to earn a living doing what I feel that I’m best at doing, and it denigrates my voice. I am all for criticism of a book that you don’t like—that happens naturally when you write a book. But when the attacks become ad hominem and are just sickeningly laced with sexism, that’s when I want to scream. I have learned to ignore it and rise above the noise, but that doesn’t mean it doesn’t still hurt. I’m turning 60 next year. If I didn’t have a tough shell, there’s no way I would have made it this long and still be doing what I do. But it still irks me and makes me feel like we have so much work to do.

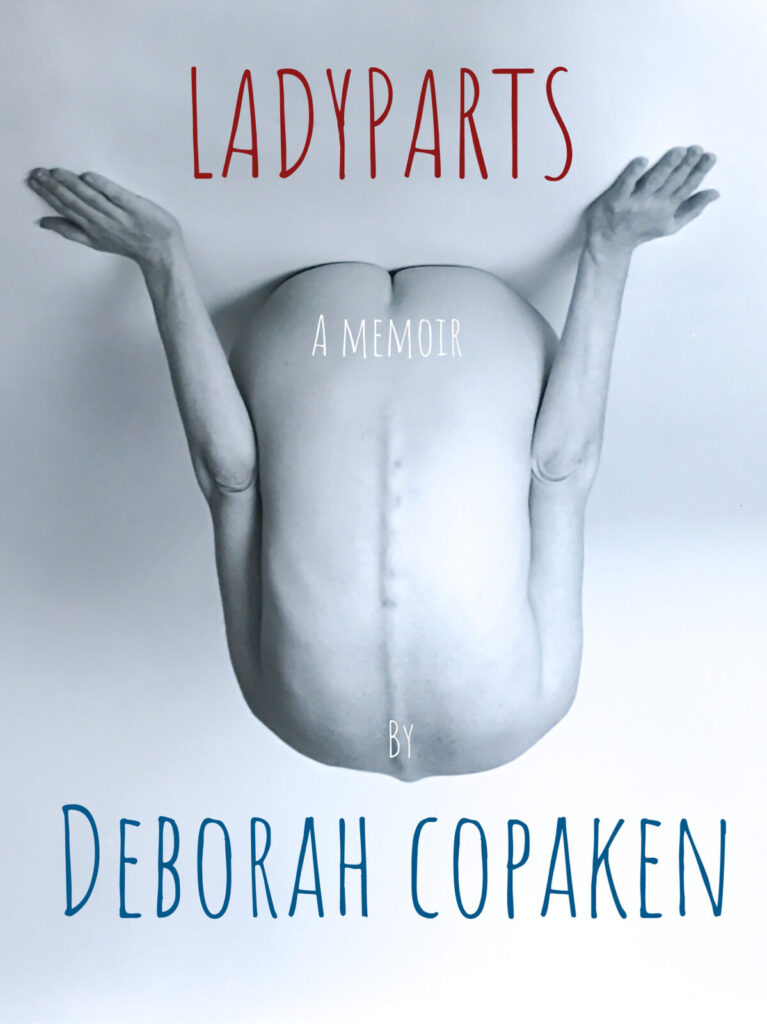

Even the review of Ladyparts was fascinating in terms of, again, the subtle sexism. Ladyparts begins with my near-death from vaginal cuff dehiscence. People with vaginal cuff dehiscence don’t often live to tell the tale. In my work, I’m trying to highlight issues that are dismissed but are important. Nobody talks about vaginal cuff dehiscence— there’s not even a national registry for it, like most diseases. People who die of it often die at home. Or they’re never diagnosed. So I’m trying to highlight this very rare, bizarre, post-operative trauma that happened to me—and could happen to somebody else—and so I start the book on this very dramatic note. The New York Times reviewer (a woman, I should add, because we women can be some of the worst tools of the patriarchy) wrote, “If you are squeamish, you might consider skipping the first section of Deborah Copaken’s Ladyparts, which describes the bleeding out of her vagina due to cuff dehiscence.” (Also it’s called vaginal cuff dehiscence, not cuff dehiscence, they even got the name of the disease wrong) “Don’t bother googling that. But let’s just say it was a near-death experience that involved kidney-sized blood clots splattering on the floor, which she collected in a Tupperware container…Is it sexist of me to be grossed out by such an image?” Yes, New York Times reviewer! It is not only sexist of you to be grossed out by such an image, it is truly sexist, misogynistic, and wrong to suggest to the 70 million monthly readers of the New York Times, via the trickery of rhetorical query, that they should be grossed out by my near-death.

What I’ve noticed with all these female journalists who take other women to task is that they often reframe their criticism inside a rhetorical query. They “innocently” ask the question that others might make, like the question I was asked [about being a slut]. This reframes their opinion that I am a slut, or that my near death was gross, as a question they are not really asking—though of course that’s exactly what they are doing. I would be lying to you if I said I was fine with that review. I was crying my eyes out. So yes, I can rise above it. I can talk to you about it now, and understand it in the context of centuries of misogyny about women’s sexuality and our vaginal blood, but I can even feel myself getting enraged all over again as I’m talking to you about it. And each time this happens, it makes you think, “I can never do that again. I can never spend another two to three years alone in a room, writing another book, only to be slapped in the face by my fellow woman.” But if I do that, if I give up, then I’m actually allowing sexism to win. And I won’t do that. Ever.

How do you see gender politics playing out in the media industry today? Has there been any meaningful change since you first entered the fields of journalism and entertainment?

I have seen meaningful changes. I think today, if somebody tried to call me a “slut” in a national magazine, as one journalist did, an editor would be like, “What are you doing? You can’t do that.”

Still, there is ample evidence and studies that show that women in their 50s are pushed out of the corporate world way more and earlier than men, and they are still paid a lot less than men. And look: not everybody wants to be a “girl boss,” but everyone wants to be paid fairly or at least as much as a man for their work. Not every woman wants to be a leader. Some women just want to do their job, be proficient at it, and go home. We should be accepting of that path, and we should give women the tools they need to work, no matter their career goals: paid maternity leave, health care, affordable child care, good public schools, and affordable college tuition. Also, the assumption in corporate America has always been and still is that a man has a woman at home to take care of things like grocery shopping, doctor’s appointments, childcare, etc. And don’t get me started on today’s government administration, which is trying to kick us back to the 1950s.

In Ladyparts, you use your body as a narrative “skeleton” to explore everything from illness and motherhood to systemic failure. Looking back, what inspired you to write this book? What did it mean to you, and what do you feel that structure allowed you to say or reveal that a more traditional memoir format might not have?

I turned to writing from TV journalism because I didn’t like the direction that my industry was going, and I wanted to keep pushing forward with the female gaze agenda that I have. That’s been my whole forward propulsion since that first college thesis; I want the world to see what it’s like to be a woman in the world. To see the world through women’s eyes. I was happily writing books for a while, and I was getting good advances. Then, again, suddenly, the publishing industry became much more about celebrity culture. Celebrity books were getting all the publicity budgets. It became much harder to make a splash in the book world or even sell a book.

My second novel was a bestseller and landed me on The New York Times list. But again, being a New York Times bestseller doesn’t necessarily translate into sustainable income. I got divorced in 2013, and then I realized how much capitalist America still favors the man in divorce versus the woman financially. I was suddenly poor because I was on my own. I ended up having to take a number of different jobs. Sometimes several at once. I even tried to get a job at The Container Store. I got rejected, even though I told them I would do anything for health insurance and an income. I was “overqualified”: a term I heard often. It was really bad for a while. I was also getting sick. I had my uterus out after a diagnosis of adenomyosis, then I nearly died from vaginal cuff dehiscence following a cervix removal, due to pre-cancer, five years later.

It all kind of percolated inside, and that’s when I realized I needed to write Ladyparts. I was looking at my body in the shower, and I saw all the different scars, and I thought, “Oh, this is from that surgery, and this is from that other surgery, and each of these marks a body part—an organ—that’s now gone, right?” And I realized that each body part could easily serve as a narrative metaphor for each period of time during which they were taken out: as I was going through divorce, and having these really hard times with corporate America, and being sexually harassed by a man who then ended up getting nominated to the first Trump White House. He ended up not getting that job because of the testimony that I gave to the FBI. In fact, he ended up getting arrested for cyberstalking another woman. But then he was pardoned by Trump on his last day in office.

So all this stuff became the book Ladyparts. I’ve now started a completely different career: I’m working on the Substack that grew out of Ladyparts and is also called Ladyparts, which is self-sustaining with subscriptions and just won a Webby! When I was freelancing for The Atlantic or for the New York Times, pre-2021, oftentimes I would pitch a story about women’s issues—recurring UTIs, menopause, those kinds of things—and they were all kind of, “ooh, gross, yuck.” Now, I am able to write what I want, when I want, and earn a living while doing it.

How does the medium you choose to tell your story through impact the overall message and storytelling? For example, do you see television reaching people in a different way than a memoir or a photo essay? Along the same lines, which medium is most effective for political and even emotional expression?

I don’t think that there’s a specific medium that is more effective than another. Each has its advantages and disadvantages. Let’s not talk about me for a second. I’m going to talk about other artists who have moved me to change, politically or personally. For example, when I watched the movie Take This Waltz by Sarah Polley, I was considering getting divorced because my marriage was just not working out. That film presented a woman who’s married to somebody she could probably stay married to if she forced herself, but she would ultimately be unhappy because they’re just not connecting sexually or on a spiritual level. That movie was really one of the first impetuses for me to take a long look at my marriage and realize I could leave it. I hold it ultimately responsible for my current joy and happiness in a relationship with a man who is equal, full of kindness and love, and works beautifully. Every single day.

We don’t know where these political messages are going to come from. We don’t always know, even as the artist, what form these messages should take or are going to take, but somehow, if we’re doing our job well, we land on the correct medium for the message.

If you could give one piece of advice to a young writer or artist, or even your younger self, what would it be?

Know where your moral line in the sand is, what you are and are not willing to do in the name of art, in the name of getting a message out there. The times that I have run into problems in my life have always been when I stood outside that line, when I felt like I was not being true to myself, who I am, and what I believe in. We all have that five-year-old girl in us, who’s confident, knows what she wants, is interested in the world, is excited to be in kindergarten, and wants to learn everything. We all have that little girl in us. Remember who you were, because that’s who you still are. What interests you as a child will still interest you as you enter your 60s. It’s all a single journey. You might have different ways of expressing those interests, needs, and questions, but you are who you always have been.