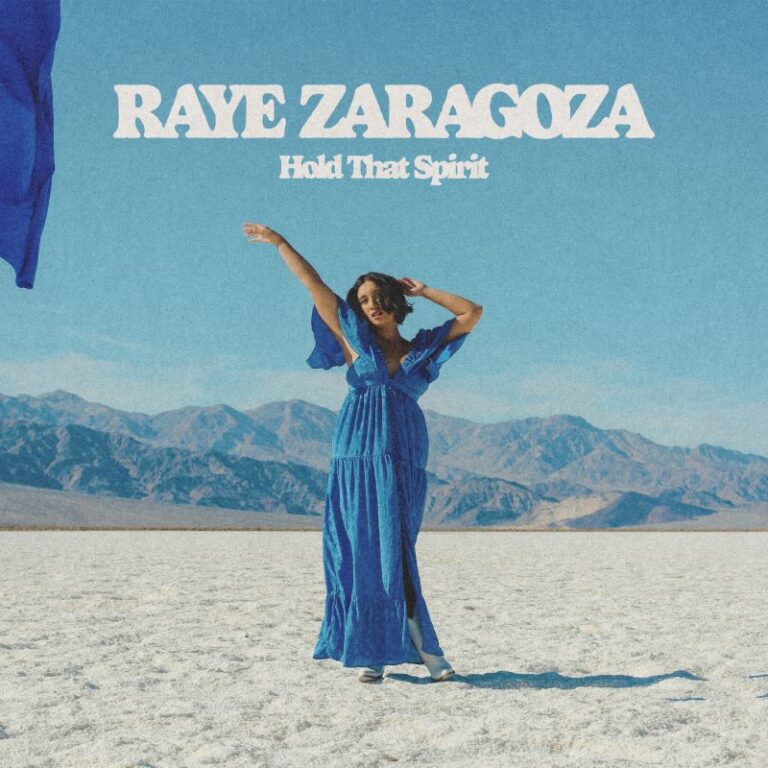

Photo Credit: Raye Zaragoza Instagram

Raye Zaragoza is a singer-songwriter and proud Japanese-American and Indigenous artist based in Los Angeles. Her music challenges traditional expectations of women and explores themes of self-discovery, strength, and joy. Her latest album, Hold That Spirit, explores the female experience and emotional healing, featuring collaborations exclusively with female artists. Zaragoza writes for Netflix’s Spirit Rangers, a Native-led animated series, and recently toured nationally in the reimagined Broadway production of Peter Pan.

Tell me a little bit about yourself and your journey: what first drew you to using music as a tool for activism and self-expression?

I’ve been doing music full-time for almost 10 years, but I started writing songs when I was 17. I’m 32 now, so it’s been a while. When I first started writing music, I was only writing love songs. But I was so passionate about other things in my life, like activism and fighting for the rights of marginalized people, especially being the daughter of an immigrant and an indigenous person. Once I started to realize that I could use music as a vehicle for expressing my anger in life and about the world around me, it definitely opened up this kind of portal—I can use this as a way to help people and make them feel more seen, especially people of color. In 2016, I wrote the song “In The River” for Standing Rock. It took off from there. My first album was Fight for You in 2017, and it was a collection of songs that were about fighting for indigenous rights. It all just came together from there. I realized that music is very powerful, and I never want to shy away from speaking truth to power in my music.

How has your identity shaped your path as an artist, and what parts of that story do you feel still aren’t told enough in the music industry?

I think that when you’re mixed race, you see the world through the lens of a lot of different perspectives— from both my mom’s and my dad’s perspectives. This has given me a very well-rounded view of the world. I’m sure I have my blind spots; we all do. Still, I really take pride in the fact that I have a unique perspective because of my identity. I think that has greatly influenced my music, and has also made it so that my music can relate to a lot of people, not only indigenous people or children of immigrants, but also women and people who just need an artist to echo back to them their discontent with the world around them, or their stressors, or the things that make them angry. My identity has a big, big part in that.

Have you found a community within the music industry that you feel like you connect with?

The folk community has been the most amazing place for me—it’s the wholesome part of the music industry. We play shows that start at 7 pm and end at 10 pm, and it’s not as much of a party culture. We still like to have fun, we like quiet music and sitting on the floor, and lighting candles. We like talking about how songs make us feel, dissecting every lyric, and getting really nerdy with songs. There’s this thing called Folk Alliance, which is a conference of folk musicians. All the folk nerds come together and nerd out about lyrics and the nuances of every note in the song. And a lot of times it’s just guitar and vocals. I love my community and the music industry, and being a part of the folk Americana scene. It’s really, really wonderful.

Your album Hold That Spirit explores the joy of reclaiming your own story. What did you discover about yourself while writing these songs?

Honestly, sometimes, my songs can be my teachers, because I will not be able to put words to how I’m feeling about something, and then I write a song, and I’m like, “Oh, that’s how I felt.” I recently wrote a song called “Who Says That’s Not American?” I was feeling so consumed with everything happening with the ICE raids and all of our immigrant neighbors being so at risk in California, and I didn’t know what to do. So, I wrote the song, which helped me put that anger outside of myself and then use it as a way to spread awareness, to shed light on an issue through social media and through a song. So for me, it’s a way of processing, for sure, and putting my pain outside of me instead of keeping it in.

You chose to work exclusively with women on this album. What does feminist collaboration mean to you in practice — and what did it teach you about making art in community?

It was almost a coincidence that this whole record was made by women. I was working with a lot of women at the time, and I thought, “Whoa. What if I made an album with all women?” I’m not sure of the updated statistics, but I know, maybe 10 years ago, 2% of producers were women. And so I’m like, “Let’s make it, let’s make an album with the 2%.” And it was just so fun. I love so many of those collaborators. It was such a safe space to write songs and create with women.

A lot of times, as women in the music industry, we have stories of being unsafe in writing sessions or in production sessions, because there was a man making advances on us. It felt like a reclamation of the divine feminine in music, and to show ourselves and the world that it’s not just a boy’s club, and that we are also good at what we do. We can do everything that the boys can do. The album was very well received. I was really grateful. My favorite part is the one-on-one responses I get from people. Someone wrote, “I’m going through something, and your album helped me get through it.” To me, that’s the most important part. It’s not about the numbers on Spotify. With folk music, a lot of our impact is very one-to-one. All the messages I got about the personal impact of the album were amazing.

As an artist, do you feel the music industry is making real progress toward more Indigenous and female representation? What changes would you like to see?

I think so. I’m a part of the Cohort Coalition with the Recording Academy for Indigenous Voices. I think that a lot of these big, major machines that are a part of the music industry, like the Recording Academy, are making an effort to make sure that native voices are heard and that we’re being represented: that we can feel like we have a seat at the table.

I definitely feel like there’s been a lot of progress there, but we still have a long way to go. I would like to see more people of color in leadership roles. It’s not just about having people of color as the artist or the talent. It’s also having them in places where they get to make the calls. Same thing, more women in power. I think it’s kind of embedded in all of us to have this competitive streak with other women, but in reality, we’re not fighting against each other. We’re actually fighting together. And so, to look at our fellow women as allies and as people who can lift us up. We’re on a team with our girls. It’s not like we’re fighting for that one seat at the table anymore.

Labels and companies are being challenged to make sure that their rosters are diverse, to make sure that their business practices are better. There was so much violence against women in the music industry. Now that’s being handled or stopped, or at least, more people are being outed for being bad people. There’s not as much normalization of violence and discrimination. So that’s good. It’s the first step. We’re on our way, but there’s still more to do.

Your career spans powerful protest songs, children’s TV, and reimagined theater. Working across so many different media and projects, do you think that there’s a specific one that is the most effective at conveying a political message?

I think that they’re all super important—between television, film, and music—to convey political messages. But, I think that music is such an amazing one, because we have so much freedom with music. We can write a song and upload it, and there aren’t many hoops to jump through, especially if you’re an independent artist. So, I think that being able to truly speak your mind is such a liberating thing in music. There aren’t really many people who can censor you—unless Instagram takes it down.

As an artist, what do you think most journalists miss when interviewing you?

I think it’s important to continue to ask, “How do you take care of yourself when you’re posting things that are political?” Or, “When the world is getting you down, how do you stay grounded? How do you stay centered? ” Because I think a lot of times, as artists, we’re so prone to burnout. What I would say is that I cannot be a good vehicle and vessel for a message and for my music if I’m not taking care of myself and getting good rest, meditating, and making sure that my mind and body are well.

What responsibility do you feel that artists have right now in driving cultural and political conversations, especially in times of political uncertainty?

Photo Credit: Jefferson Public Radio

I think that artists have a huge responsibility because people look to artists. I don’t know why. It’s not like we have all the answers, but a lot of times, people look to us as influencers. I think it’s very important for artists to really think about their imprint on the world. It’s very important to me to be seen as someone that the youth can look up to. I try to be a role model. I respect when artists want to stay silent about certain things, but I also have so much respect for artists who aren’t afraid to speak up.