Ari Weinzweig was born in 1956 in Chicago, Illinois. He is a co-founder of Zingerman’s, a gourmet food business group in Ann Arbor, Michigan, comprising eateries such as Zingerman’s Delicatessen, Miss Kim, and Zingerman’s Bake House. He is also an entrepreneur, author, and speaker, having published books including A Lapsed Anarchist’s Approach to Building a Great Business: Zingerman’s Guide to Giving Great Service and A Lapsed Anarchist’s Approach to the Power of Beliefs in Business. He was recognized as the “Who’s Who of Food & Beverage in America” by the James Beard Foundation in 2006 and received the Lifetime Achievement Award from Bon Appétit magazine in 2007.

How did you become involved in the food industry, and why did you decide to open Zingerman’s?

I came to Ann Arbor from Chicago, where I grew up. I studied Russian history and anarchism [at the University of Michigan]. Then, I graduated and didn’t want to go home, so I decided to stay here. One of my college roommates was waiting tables at a restaurant, so I decided to apply for the same job he had. They interviewed me and said they’d call, but they didn’t. After two weeks or so, I went back and reapplied as a busboy. Once again, they didn’t call. I was running out of money, so I went and offered to do anything, and they offered me a job washing dishes. My business partner, Paul Saginaw, was the general manager—it was his first day and mine. I really just lucked out because I stumbled into work that I love and met great people. I started [washing dishes], then prepping and line cooking, and then I ran kitchens for a few years. Then, in the fall of 1981, I reached a point where work was less inspiring, and I could sense it wasn’t going where I wanted it to go. So, I gave two months’ notice with no clue what I was going to do next. Paul had left and opened a fish market. He didn’t know I had given my notice, but he called me two days later, and he said that there was this little building coming open near the fish market that we should go check out together, and we did. Four and a half months later, we opened Zingerman’s.

How did you become interested in anarchism, and how do your principles influence your business and leadership practice?

I studied anarchism a lot. I liked it, and the University of Michigan has the largest anarchist collection [of historical documents] in the country. When I started to manage people at Zingerman’s, I tried leaving them all alone in the naive belief that they would do the right thing, which didn’t work out. Then, I started to study the progressive leadership thinkers of that era—Max DePree, Margaret Wheatley, Robert Greenleaf, and Peter Drucker. For years, when I would speak or introduce myself, I would say I was a lapsed anarchist because I still believed in it, but I didn’t practice it, and everybody would laugh because nobody really knows what anarchism is.

Fast forward to 2008 or 2009, I was working on what became A Lapsed Anarchist’s Approach to Building a Great Business, which is the first book in my leadership series. Deborah Dash Moore, who was the head of Jewish Studies at UMich at the time, invited me to speak there. I had just written this long essay on the history of Jewish rye bread—she’s like, “I want to call it Anarchism and Rye.” When I got three months out from the talk, I had this realization that I hadn’t looked at my anarchist books in 25 years. At most business conferences, nobody knows what it is, so it doesn’t make any difference—I’m the most knowledgeable one in the room. But in the Jewish Studies Department at UMich, they all know who these [anarchists] are.

So, I got all my books out and started to reread everything, and it blew my mind: 1) because so much of what we had created was unconsciously aligned with a lot of what was in there, and 2) because so much of what is anarchism is now looked at as progressive business, but nobody makes that connection. Self-organizing work teams, flattening hierarchy, employee engagement, and purpose—these are all common themes in the modern progressive business world—often done disingenuously—but when done sincerely, they’re a lot aligned with anarchism. I realized that I was the only one weird enough to be reading Emma Goldman and Peter Drucker at the same time, so that parallel started to show in ways that nobody else would have noticed. Then, I just did what awkward, introverted history majors do best, which is to start reading more books. I started studying and studying, and I haven’t stopped since. There are just a lot of really important principles, and I try to keep putting them into practice. I’m the only one here who’s going to bring them up. It’s not like the rest of Zingerman’s talks about anarchism, but it’s really just trying to apply it in a meaningful, down-to-earth, imperfect way.

Does implementing anarchist principles within your restaurants impact the food itself?

One of the key beliefs of anarchism that informs my work is the belief that your means need to be congruent with the ends that you want to achieve. So, in other words, you need to behave in ways that are aligned with what your desired outcomes are. That idea came from the schism between Marx and Bakunin in the 19th century, where the Bakunin-led anarchists asked: “How can you have a dictatorship over a proletariat and achieve freedom?” If you want freedom, you have to start with freedom, not dictatorship.

That principle informs everything. If we want dignity, then we need to treat everything with dignity, including the food. If we want great service from the people who are working at the front door or the counter, then we need to give them service. Everything needs to be aligned. The food is treated with dignity. From the beginning, we’ve always been focused on full flavor, which we define as complexity, balance, and finish, and also on traditional food. We’re always trying to go back to the old ways, but not in lieu of appropriate uses of technological improvements (some things, such as coffee, chocolate, wine, and olive oil, have been improved by technology). However, most food in the 20th century was demeaned by technological means in the interest of a lower price and a longer shelf life.

And I’m a history major, so I’m always asking, “Where did this come from?” Everything includes everything. So, the food includes its race, gender, religion, economics, globalization—they’re all coming alive.

Are anarchist principles more suited to some industries than others?

I’m not in other industries, so it’s speculation, but my belief is that anarchism is really aligned with human nature. It was presented as a reaction to the dehumanization of the Industrial Revolution. So, I think it’s aligned with just being a person, too. I’ve realized long ago that a lot of our approaches work because they’re actually aligned with human nature and with how people want to live outside of work. I didn’t go to business school, but my takeaway from being around a lot of [the anarchist literature] is that it is antithetical to how you want to live your life. You’re learning there that you need to invert [your behavior and beliefs] when you go home. When you learn about beliefs at work and how much impact they’re having, it changes the relationships you have. When you learn about compassion, kindness, and dignity, it’s the same at home, and people, in a good way, use it with their kids. They use it with their significant other. These principles are trying to help people be true to who they are, as opposed to the pressure to conform and be something they aren’t.

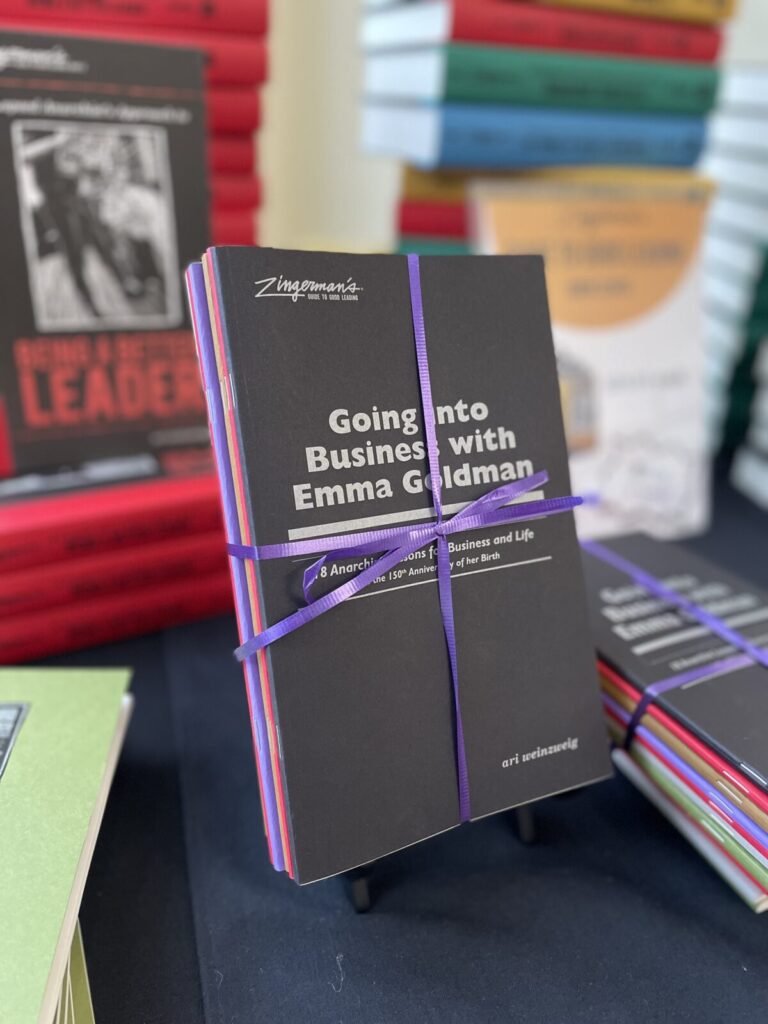

In Going into Business with Emma Goldman, you discuss the importance of designing work that brings joy, purpose, and creative passion. How do you ensure that everyone at Zingerman’s truly loves their work?

You can’t, and I’m not here to tell you that everyone loves their job every day. It’s a lot on the organization, but it’s equally on us as participants in the organization. If you’re not looking for joy and you don’t want to find it, you won’t. Of course, there are healthier and less healthy workplaces. But, the idea is to create a culinary ecosystem where joy is more easily found, where it’s talked about, and people are encouraged to pay attention to it, as opposed to a more industrial setting where it’s like, “shut up and do your work” then go home and enjoy what you do with your kid only on a Sunday instead of understanding—back to anarchism—that you’re human and everything should have some joy in it. Everything should be purposeful. It’s not only about finding purpose on your day off.

What was your favorite Jewish food to eat growing up? What is your favorite thing to eat at Zingerman’s now?

Growing up, potato latkes, maybe chopped liver. Now, I eat a lot of olive oil, bread, vegetables, fish, and pasta. Zingerman’s makes and sells all of that. I’m looking right now at bags of pasta from the Mancini family in the Marche region of Italy. They’re the only farmstead pasta maker in Italy. They grow wheat and make the pasta all organic with it, and it’s old school, bronze dye extruded, so you get a rough, sandpapery surface. The modern ones are all through Teflon, which is faster and cheaper but makes super slick pasta, which is why your sauce at home is always at the bottom of a bowl. That’s what I cooked at home last night at about midnight because it’s so awesome.

Do you see food as an effective medium for political expression?

One of the many interesting things that became clear to me as I did this second round of anarchist stuff came from a quote from Gustav Landauer, a German, Jewish, pacifist anarchist who was kicked to death by the German Army in 1919 when they overthrew the progressive government. I couldn’t read his work when I was in school because it was still only in German. But, in the meantime, [Landauer’s work] got translated by Gabriel Kuhn into English. When I read it, there was a lot in his work that really informed my thinking. One thing he said was, “We have no political beliefs. We have beliefs against politics.” It helped me understand that anarchism—and obviously, there are a million interpretations of it—is not a political system; it’s a belief system. It’s really about day-to-day human interaction, not about taking charge. It’s the opposite of taking charge. I think everything is related to everything. So food is art, food is politics, food is human life. Food is history. It just depends on what part of your brain you want to view it through.