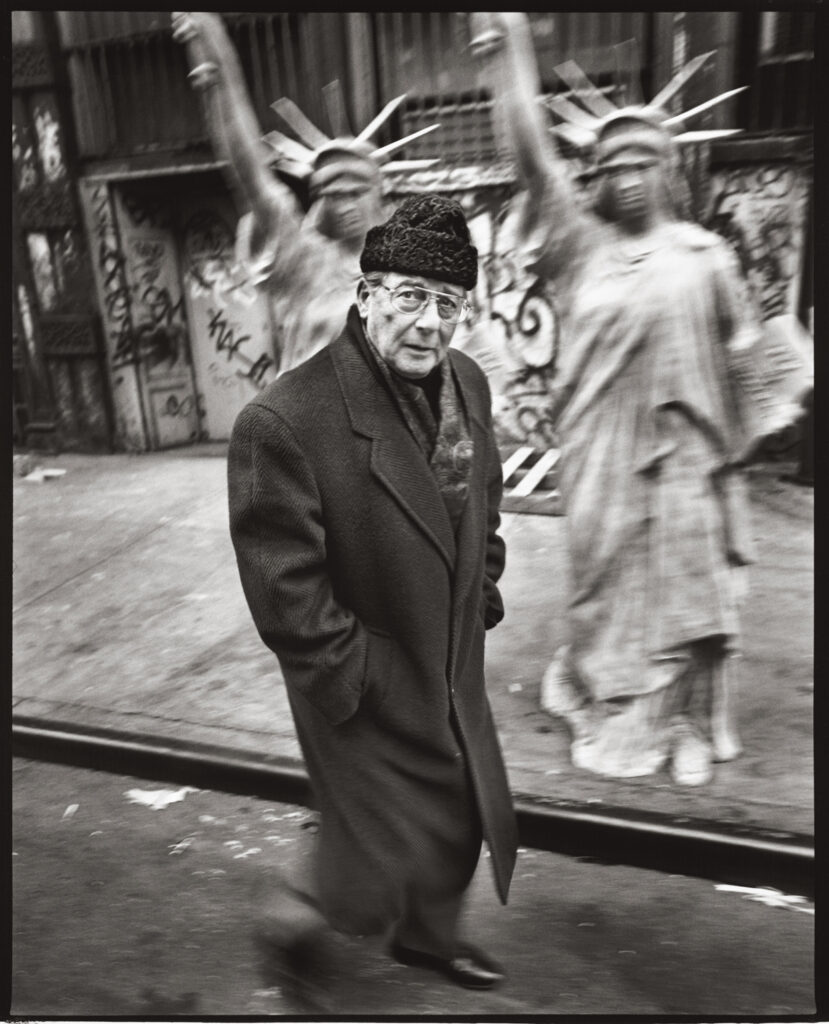

Mark Seliger was born in Amarillo, Texas, in 1959. He is an acclaimed photographer, most recognized for his portraiture, and was the chief photographer for Rolling Stone from 1992 to 2002. Afterwards, he worked at GQ and Vanity Fair until 2012. In addition to his editorial work, he has published several books, including When They Came to Take My Father: Voices of the Holocaust and On Christopher Street: Transgender Stories. His photographs have been showcased at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C. and the National Portrait Gallery in London, among other museums.

What sparked your interest in photography, and how did you enter the field? Why are you especially drawn to portraiture?

When I was a teenager, my mom and dad signed me up for a darkroom class at the Jewish Community Center in Houston, Texas. [At first], I fell in love with the idea of being in the darkroom, but I didn’t really care much about taking pictures. That’s where I started, but then I finally figured out how to take pictures. I enjoy the process of working and collaborating with people I find. There’s a very deep well of different approaches I can take with portraiture, whether it be in the studio or environmental, whether it’s documentary or entertainment. So, it just opens up a wider door for me.

Could you please describe your book, On Christopher Street—how did you come upon the idea, and what were your hopes in capturing it?

Christopher Street came from the simple idea of noticing that my neighborhood, specifically on Christopher Street, was evaporating and being gentrified. In my opinion, Christopher Street is almost like Ellis Island for blurry gender lines. Once I went out and started to talk to people and photograph them, many of my subjects revealed that they were transgender. Then, through interviews and getting to know them a little bit better, I felt like that was more of an interesting story to tell.

The Christopher Street project, as a whole, is something I’m really proud of because it was something that I didn’t know anything about. By taking the time and getting to know my subjects, I was able to really understand a lot of the journey that they’re going through. What you first see isn’t necessarily what it is. Exploring their stories with them and finding a way to express who they were made me want to focus on the idea of them being seen for the very first time as their authentic self. To me, that was the biggest part of a successful experience—to be able to tell that story to other people.

In “The City That Finally Sleeps,” people are almost entirely absent. How did the shift to landscapes alter the impact and perception of your photographs?

That was a real departure for me because I’m typically known for photographing people. But what I loved about this project was that New York City and these destinations were very iconic, and yet there were no people. I felt as if it was my obligation to go out and record, probably the only time in my lifetime, hopefully, the city in that state of rest. I didn’t have to ask anyone any questions. I just went and took the picture, and it was like a movie set because nobody was around. I had a chance to really experience the stillness. It was a record, but it was also almost like a portrait of the city without people in it, the city being the portrait.

How does your creative process change between your editorial/fashion work and documentary projects?

It’s all paintbrush in terms of the tools that you use. Portraiture is more about my subject matter, so I do a lot of studying and pre-planning on the front end, then getting to know who my characters are, and finally, concepting. Sometimes, it’s a very reductive moment, and sometimes, it’s a very involved moment of creating a scene. For my fashion work, it’s not dissimilar. But, instead of people being the hero, fashion is the hero. My documentary work more so relies on a common thread of a storyline—getting to know what the story is on the front end so that I have a directive and a direction of where the entire piece is going to go, and then thinking in terms of that being a bigger body of work and documenting more of a culture.

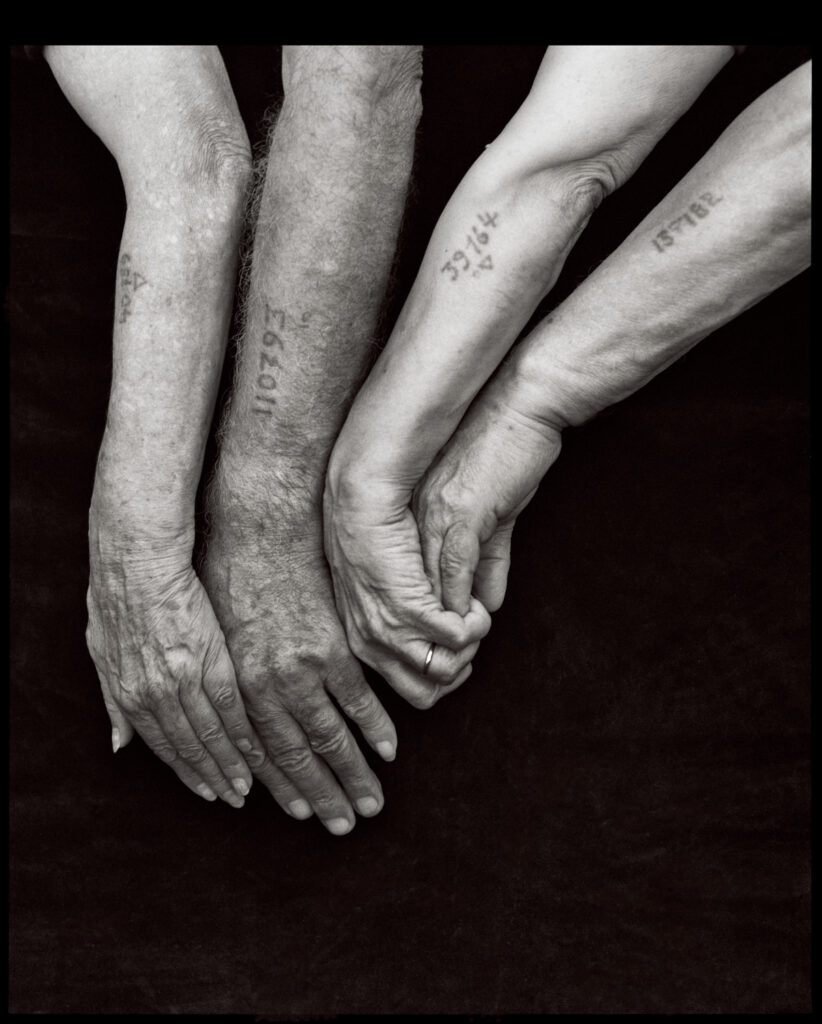

In When They Came to Take My Father: Voices of the Holocaust, you portray a wide range of emotions in your subjects. What guided that choice, and do you believe that photography can serve as a more humanistic retelling of history?

That was my first book. It was inspired by three brothers who owned a bakery where I grew up. I was definitely very aware of the Holocaust through my early Jewish education. When I would go in with my folks to pick up food or bread, I noticed the tattoos on the brother’s arms, and I thought, one day, if I ever have an opportunity, I’d really like to be able to tell their story and other people’s stories of what it was like to go through something like that.

I think we’re all very visual, and, especially now, more visual than ever. Photography gives you a door to open to be able to start the process of empathy, whether it shocks you, greets you, smiles upon you, or disgusts you. You need that immediacy to evoke a certain interest, and so it’s the preemptive entry into whatever story is being told. It works as a companion piece to a story in order to be able to illustrate a point more honestly and truthfully.

Do you see photography as an effective medium for political expression?

Absolutely. Even though there are new forms of ways you can manipulate a photograph, the potential of photography remaining an immediacy to truth is still prevalent. It really is up to the photographer to make the decision of how they want to present it, but I like and prefer the honesty of an image. I don’t mind theatrical or fantastical, but I feel like, in a day and age where there’s a lot of ability to change the way a photograph looks, keeping it in camera and trying to do less with it instead of radically changing what you have is my preference.

I think [political meaning in art] can be a very subtle experience. I think it can be abstracted in terms of more of an observation rather than a direct opinion. In photography, we tend to focus more on observation and less on personal opinion, but I think it can help establish a greater understanding of the political landscape.