Born in Chicago, Illinois, in 1965, Dread Scott would become an artist whose work would ignite national outrage, reach the Supreme Court, and redefine the limits of political art in America.

He attended the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and works in a variety of media—including performance, photography, painting, and printmaking. He is focused on creating revolutionary art to “propel history forward.” His work has been shown in exhibitions at museums such as MoMA PS1 and Cristin Tierney Gallery, and is part of the collections of institutions including the Whitney Museum, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and Washington D.C.’s National Gallery of Art.

Why did you start creating?

Somewhat by accident. I’ve been an artist for years. I grew up in a household where my dad, before I was born, was a professional photographer, and in my lifetime, was a really serious amateur. So, I grew up around cameras—my parents gave me a good camera when I was about 12. I was also a terrible high school student. I was smart, but I didn’t do very well, and so I couldn’t get into MIT or Caltech. So, I thought, “Well, I’ll be a photographer.” I ended up at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, and I fell in love with photography. Not doing well in high school was a great accident that set my life on a path that I’ve been walking since then.

Your art is centered around community engagement and participation: how does this focus relate to your beliefs about the purpose and power of art?

The majority of my work is displayed in galleries and museums, but a lot of it has been community-engaged in some way. All of my work, regardless of whether it’s community-engaged, involves big questions confronting humanity and trying to help people see the world in new and radically different ways; hopefully, how the world could be far better. In addressing these big social questions, I’m trying to help people connect with a movement for revolution in a certain sense. And so in that context, there’s a lot that people in an ordinary community, as opposed to just me as an individual artist or even the art community, know. So, working together, we could both learn something. I can make art about some of these big questions in ways that I couldn’t just on my own.

For example, a project like Slave Rebellion Reenactment, which was presented publicly in 2019, reenacted the largest slave rebellion in the history of the United States in 1811. It involved 350 people. Part of doing that was to connect with all sorts of ordinary folk who had a tremendous reason to want to embody a history of freedom and emancipation. Some of the people were relatively recently in prison, and said afterwards, “I was a prisoner, and now I’m embodying freedom. I’m fighting for emancipation.” How does a slave revolt from 1811 connect to our present? How does somebody who was locked down by this system see that differently than somebody who might not have that experience?

There was a group of virtually homeless people who participated, and it was deeply meaningful for them to embody fighting against the system. There was the aunt and uncle of Oscar Grant, who became known to the world because he was killed by the police in Oakland, and shot while handcuffed, lying face down—it was one of the first recorded cell phone videos of the police murdering somebody. They are activists who are fighting for justice against police violence, but it was really important for them to bring that experience into this slave rebellion.

There are people in my projects that have a life experience and an understanding that is different to mine, so my thinking about these questions on my own is different than when I’m talking with people, some of whom have caught hell under this system, which is a system that is based on oppression and exploitation, and was founded on slavery and genocide. Drawing on the diverse, complex, varied life experiences of other people is important to my art.

How has audience participation or feedback changed your understanding of your work?

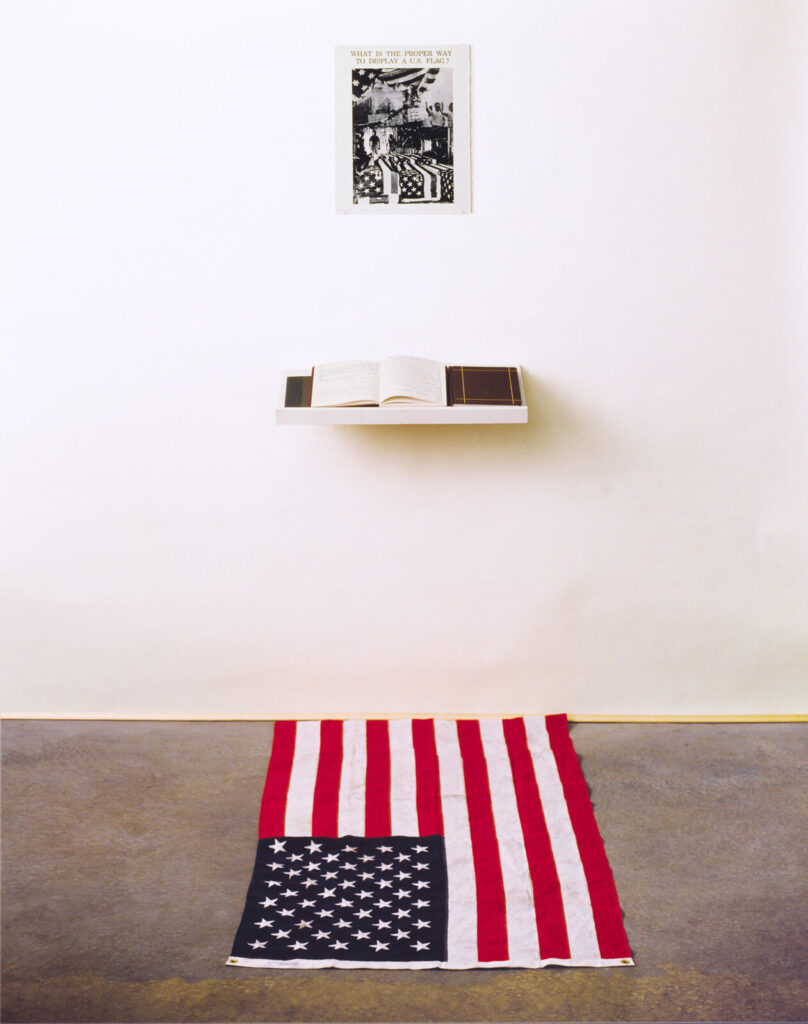

I think that a good artist should pay attention to how the public and audience engage in response to their work. It doesn’t mean that we are a Gallup poll, or we’re just taking a litmus test of what people think, but it is important to listen to people. The first project that I did that had national attention was called What Is the Proper Way to Display a U.S. Flag? It was an installation for audience participation that focused on what the United States, patriotism, and the flag represent.

That piece was both loved and hated. When it was shown at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, where I was an undergraduate student at the time, it got bomb threats. I got death threats. There were laws passed to outlaw it both at the time and then shortly thereafter, on a federal level. The President of the United States, George H. W. Bush called the work “disgraceful,” which I thought was a tremendous honor. It was like, “Wait, the President knows I exist, and he doesn’t like what I’m doing. Well, this is a great career. I want to do this for the rest of my life.”

There were people who were demonstrating for the work, including Vietnam veterans, who were really in support of what I was doing because their experience of being sent to fight a U.S. war of occupation and domination was not something that they were proud of—at least the Vietnam vets that I was meeting. A lot of people in the arts saw that and saw the people who were calling for my death, who were very vocal but also openly racist about it, and said, “Oh, these people don’t understand the work. This is about freedom of expression and the First Amendment.” It was not. The work was about U.S. patriotism, what the United States represents, and what the U.S. flag represents. So the people who were calling for my death, they didn’t like the work, but they understood it in a way that some in the art world didn’t understand. In the end, it was really important for me to listen to both of those experiences.

But also, again, to the people who catch some of the hardest hell under the system—people in housing projects who were calling into radio talk shows and not only giving me political support, but also giving art criticism and telling me how they understood the work, and how it made them feel. Just to be clear, people in housing projects don’t normally think about what contemporary conceptual artwork is, and especially not by an unknown undergraduate art student. But when they are presented with this work, they can engage with it. They’re like, “Oh, this is actually interesting. This is talking about ideas that matter to us.”

Some of the people could say things like, I came to see this artwork, and it made me think of how the police shot my brother and then walked over to kick over his body “to make sure the n****** was dead.” Then said, “That cop was wearing a flag patch on their arm,” and thanked me for the opportunity to engage that question and stand on the flag. Having my feet and my heart planted in those types of understandings is important to me. To really try to separate out what people are saying about my work, and not just say, “Oh, I did this. I don’t care what people think,” is important to me. But, no, this is hitting a nerve in society on our important social question, and I thought I was doing it quite successfully.

How do you determine which medium to prioritize for a specific project?

It occurs for two reasons. One, if I do the same type of art over and over and over again, I’m bored with it. I also think my audience would be bored with it. So, part of it is just keeping my intellectual curiosity. I also think about what the best way to address a particular question is.

When I wanted to do Slave Rebellion Reenactment, I thought the best way to address this major historic and hidden event would be to reenact it, to actually engage with the public, and not hire a bunch of actors, but to do something site responsive in the same location as the rebellion that actually happened. That would be better than doing a screen print of it, because I could bring community into the project, whereas, something like A Man was Lynched by Police Yesterday, which is a banner that draws on the history of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), a national civil rights organization that, in the 1920s and 1930s, used to fly a banner that said, “a man was lynched yesterday” anytime anybody was lynched.

I made an artwork that added the words “by police” to the NAACP banner that they made in the context of the civil rights movement. I was bringing their banner into a fine art context, but also a public fine art context. It wasn’t community-engaged. I just made this banner; it was initially put inside a gallery and then outside of a New York gallery, right at the time that the police had killed two people, and it intersected with the Black Lives Matter movement in a really interesting way.

The police had just killed Alton Sterling and Philando Castile in two separate incidents about 36 hours apart, and people were really upset about it. I didn’t know how the piece was going to intersect with that political movement [and moment], but I did know that this was something that would touch on a really important social issue, and that putting it outdoors in the midst of this sudden upheaval was something that would resonate with people.

You make the work thinking, “How is this going to be perceived?” Sometimes I’m more directly trying to speak to a traditional art audience, and sometimes I’m trying to speak to a broader audience. Sometimes my work shifts back and forth between audiences based on where the work is shown, but it is really about thinking of the best way to address a question. I don’t think there is one medium that is the best. Some artists feel they can do what they do best through painting, for example, and spend their whole career doing that—and some of that work is fantastic. I have a wider palette.

Do you see dissension as an essential component of your art?

In a broad context, yes, but I’m largely making work for the majority of humanity, and for their deepest interest. Many of those people don’t live within the borders of the United States. It’s not the venture capitalists and titans of industry. It’s people who grow food and build houses and make art. It’s a broad range of people—middle class, down to the working poor or unemployed. It includes undocumented people. It includes people of all genders and ethnicities. I’m trying to make work that, when they see it, they see their world reflected. I also want to make work that brings hope and joy.

It is sometimes very much [about] dissenting on a particular social question, because my work challenges a world based on capitalism—a world where a small handful of people control the wealth and the knowledge that humanity as a whole creates. My work asks questions such as: why is it that a president on one side of the ocean can drop bombs on a country that hasn’t even threatened them? Was it because they were going to get nuclear weapons? Well, the United States has nuclear weapons, and it’s the only country that has bombed a civilian population and did it twice. And yet, the United States [self-imposes] the moral authority to determine who else should have the right to do that. My work challenges that framework.

Some of my work is very much about dissent, but a lot of it is also calling on people to imagine how the world could be different and better. So, with Slave Rebellion Reenactment, that wasn’t dissenting. It was just talking about history and people getting free. That’s not dissenting in the same way, but it is calling on people to dream about what the world could be if there were no America—if it didn’t have the disproportionate influence that it does in the world. So, there’s dissent, but there’s also joy and hope.

A project that I did recently at the Venice Biennale was called the All African People’s Consulate, and it basically created a council embassy of sorts for an imaginary Pan-African, Afro-futurist union of countries. Like any consulate, we issued passports and visas. If you were African—meaning a citizen of one of the 54 countries of Africa, regardless of your race or ethnicity—or, if you were black, Afro descended, living anywhere in the world, you qualified for and could apply for a passport. If you didn’t meet that criterion, you could apply for a visa to visit this imaginary place. That was posing a question. People in Europe could cross borders all the time. Within Europe, you don’t need a passport at all to go from France to Belgium. It’s easy for Europeans to travel to Africa; often easier for somebody from Portugal to go visit Kenya or Nigeria than it is for a Nigerian to visit Kenya or a Kenyan to visit Nigeria. And so, my work was posing questions about belonging, about travel, about migration, about who determines these borders. It’s dissenting in the sense of why is it that it’s easier for some to travel? For Africans and Afro descendant people, it was forging community in a very special way. It was a very hopeful piece, and it wasn’t dissenting in a traditional sense.

Tell me about your work, What is the Proper Way to Display a U.S. Flag?, and its resulting legal complications with the Flag Protection Act and the Supreme Court case United States v. Eichman? How did that experience change your understanding of your role as an artist?

So, the artwork is conceptual. It was an installation for audience participation—a simple work that consisted of three key elements. The first was a 20 by 16 inch photomontage on the wall and had text that said “What is the proper way to display a U.S. flag?” on it. Below that was a shelf with three books on it, where the audience could respond to that question. On the floor was a three-by-five-foot American flag that people had the option of standing on as they wrote their responses to the question. The photo montage, in addition to the text, had images of South Korean students burning American flags, holding signs saying, “Yankee, go home, son of a bitch.” And below that were coffins draped in an American flag coming back from Vietnam in a troop transport.

The work was simple, asking the audience to engage with the question. And they did. There were hundreds and hundreds of pages of people responding across several shows. But, when it was shown at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, where I was an undergraduate student, there were many protests for and against it, and bomb threats and death threats. There were laws passed to outlaw it, both at the time the work was on display, and then afterwards, the Flag Protection Act of 1989 was passed, but when it was being discussed on the floor of Congress, they specifically cited my work as a reason why they needed the law.

The history is a little complicated. There was a flag burning that happened in 1984 in Texas that went to the Supreme Court, and because of the political battle that was waged around that case, called Texas v. Johnson, the Supreme Court ruled that flag burning was protected speech, covered by the First Amendment, [and thus, that state laws prohibiting it were unconstitutional].

That Texas law [challenged in Texas v. Johnson] was written in a very weird way; it allowed a civilian to bring criminal prosecution against somebody if they were offended by seeing the flag burn—there are many ways that that law would be unconstitutional. So, Congress tried to pass what they pretended was a content-neutral legislation with the Flag Protection Act of 1989, which was trying to overturn that Supreme Court decision and specifically included wording that would have outlawed my artwork.

For me, it was an indication of the power of art. People from the housing project waited in line for an hour to see the artwork, and then called a talk radio show to give feedback. That’s amazing. And the President of the United States called it disgraceful. Also, seeing Congress effectively tear up the First Amendment to try to suppress an artwork by a previously unknown undergraduate art student from a Midwestern art school actually showed that the powerful could be threatened by artwork and the powerless could be inspired by artwork. If you previously had asked me whether art could matter or change the world, I would have said yes. But, if you really pressed me on it, I would have qualified that by saying yes—if you are Steven Spielberg or Chuck D, the leader of Public Enemy—because they reached millions of people, and fine art, on a good day, was only seen by a few hundred people. But then, here was the President calling it disgraceful, people lining up to see it, and Congress outlawing it. [I realized], “Wait, fine art can matter too, if it’s really good.” I’ve been trying to make art that matters that much ever since.

How involved were you with the Supreme Court Case itself? How did you respond to it?

The law passed, and then several others, and I burned flags all across the country the second the law went into effect because the government was saying that the Flag Protection Act was needed because there were “five or six nasty, terrible flag burners,” and that the whole country was demanding that they be protected from that. So, the second the law went into effect, people all over the country burned flags, and the government didn’t arrest anybody, in part because they previously said that the public was demanding this law, and yet, the public was dissenting. So, others and I said, “If they didn’t arrest us for that, let’s go to a place that they can’t ignore. We’ll burn flags on the steps of the Capitol.” And that happened two days later.

They did arrest us for that, and it went straight to the Supreme Court. So, that was a huge political battle that the other people and I who burned flags on the Capitol, as well as people from a separate case from Seattle, really waged. We were on TV talk shows; we were speaking on college campuses and in high schools; we were doing radio interviews; we were going to rallies.

One of the people was Joey Johnson, who was a defendant in the 1984 flag-burning case, Texas v. Johnson, but also Shawn Eichman and Dave Blalock. Shawn Eichman was another radical artist, and Dave Blalock was a Vietnam vet. We all burned flags on the steps of the Capitol. We were part of an activist organization that was leading people to say, “Look, this is not a few nasty flag burners against the American public. This is all people who don’t want to live in a country where you can’t criticize the flag or the government.” The government was trying to make patriotism mandatory, where there was only one permissible view of the flag. So, we were going to fight that. We had a great legal team, which included the legendary Bill Kunstler, who defended all sorts of people that had gotten into trouble with the U.S. government in various cases, but also Ron Kuby and David Cole, who would later become the National Legal Director for the ACLU.

We were all in the court during the oral arguments, and then continued our activism, because we realized this wasn’t going to be decided on the question of law, but largely on public opinion. They ruled that this [federal] law was unconstitutional because criticizing the flag or using it in artwork or burning the flag is protected by the First Amendment.

What are the strengths and weaknesses of art and performance as a method for political expression compared to more traditional practices?

I think that you need both. There hasn’t been any social change—at least that’s been for the better—that I know of, that hasn’t had some sort of art that is a part of it.

Art is tremendously important for people to hope, but also to find enjoyment, and to understand the world. But it’s not the same as the demonstrations or the organizing. If there weren’t people getting on buses to break the back of Jim Crow, that wouldn’t have happened. Yet, if there weren’t people singing, “change is going to come,” those people wouldn’t have been as inspired to be on those buses and felt the strength and solidarity to continue the movement in the face of having fire hoses turned on or having their bus fire bombed. Would Mamie Till-Mobley have decided to have an open casket of her son Emmett Till, showing her son’s bruised and battered face to really depict the horror of lynching and put a national spotlight on that, if Strange Fruit weren’t part of the zeitgeist?

There is a real relationship between art and culture and the broader political movement. I don’t think art by itself changes the world, but there won’t be any good social change if there isn’t art talking about these profound questions.

What do you consider to be the role of the artist during times of political uncertainty?

I think people have to choose what they want to do. There are a lot of artists who make really good art that aren’t choosing to intervene in any great political question or battle. But then some do choose to. Paul Robeson, who was an activist, an organizer, an amazing sportsman, but also a beloved singer and actor, said, “The artist must elect to fight for freedom or for slavery,” and he knew what he chose.

I think that’s a real litmus test for those artists who are thinking about the world; this is a world with profound injustice, inequality, and exploitation. Artists are typically part of the section of society that has the relative freedom to work with our heads and with ideas. We aren’t showing up at a factory 16 hours a day to try to put food on the table. We are, in a broad sense, middle class, even if we didn’t come from that. By the time our art is out there, we have the relative freedom and luxury to do that. If you have that freedom, do you reinforce the division in society? Or, do you try to say, I want to make work so that there isn’t a world where some people are condemned to work with their hands in back-breaking conditions all day and all night, while others are benefiting from that.

Right now, we’re living in a time where the President of the United States is saying that immigrants are the problem in American society. But undocumented immigrants pick our food. They build the buildings we live in. They do the work that a lot of other Americans don’t want to do. They’re the lowest rung of the construction industry. They clean the toilets, they bus the tables, and they are in the back of the kitchen. They’re a vital part of society and yet terrorized and attacked by the President of the United States, and their families are being split up.

The question is where artists stand in the midst of this. Do people say, “I’m just happy they’re not coming for me,” and make whatever art they want? Or, do they say, “I’ve got a responsibility because they aren’t coming for me right now, and I’ve got the relative protection of society as a whole that believes that art should be critical.” So, I will sing songs about this. I will paint pictures about this. I will write poetry about this. Those are choices that we have as artists, and I hope that increasingly, artists decide to put their heart and their feet planted with the people.