Janeil Engelstad was born in Seattle, Washington, in 1961. She has an MFA in photography from New York University and the International Center of Photography’s dual program. Her work spans different media and is focused upon making “a generative and positive contribution to people and the planet.” Her art has been both exhibited in and produced in partnership with institutions such as the California Museum of Photography, the U.S. Department of State, and the International Center of Photography. Alongside creating artworks of her own, in 2010, she founded Make Art with Purpose (MAP), an organization centered around artists producing collaborative projects that explore social and environmental issues.

What sparked your interest in creating art?

I think it began with my parents. It was a creative household. My mother was an artist, and my father created and built things just because he did. We were encouraged to explore art and take art classes. Although in school, I leaned more towards literature, history, and even politics. These two [interests] finally merged, but initially, it just came from being around creative people and having stuff to make stuff with as a child.

Why did you create Make Art with Purpose (MAP), and how does it help you work towards your artistic mission?

MAP produces projects that use arts and design to engage social and political themes. Our projects range from very small, grassroots projects that are very community-oriented to widespread projects that involve government, university, and foundation partners. It can also include many artists or designers and span multiple media over several years. It could be a zine that tells stories, a mural, or even a theater project. We are working on one now that looks at the stories of women of color who have survived breast cancer, which are very different from what Caucasian women usually experience due to access to treatment and information.

I created MAP as a structure to bring people, organizations, ideas, and positive action together. I was doing that work as an independent artist, and in order to fund the projects I was creating, I needed to ensure that one of the partners could act as a nonprofit sponsor. I found that having a structure [through MAP] allowed me to still work with partnership, but not with the logistics part of it.

MAP helps me work towards my mission because it creates a space for people to come together and collaborate who might not otherwise come together, and in that process, it builds community and offers places for engagement that might not otherwise happen.

What are the strengths and weaknesses of art as a method for political expression compared to more traditional practices?

Artists are storytellers. No matter what medium or what they’re expressing, they’re telling some sort of story that’s personal or just observational or, sometimes, a combination of both. All of us carry stories, and we often connect with other people through stories. So, this is really the strength of political art, or of working on political ideas or activism through or with the arts. I think if you look back at the most recent presidential campaign, one of the challenges faced by Kamala Harris was getting her story out in such a truncated time frame, as she was running against someone who had already gained so much media exposure and had a known story. The idea of storytelling is really key when it comes to political art, but all artists are also creative thinkers, idea-generators, and problem-solvers. Some of the most political art also considers aesthetics. If you have training, aesthetics, and an understanding of art history, you can make your art stronger and perhaps more impactful.

I think that a weakness would be to look at art as a way to directly solve political problems. Artists are the ones who are going to save us in some situations, but [generally] I think art is part of a larger movement.

What political themes are you most interested in addressing and exploring through your work?

That changes all the time. It depends on what’s going on in the world. Often, I think, “Oh, I could have an impact here.”

I can remember when gun violence exploded in schools across the United States with Columbine in the late 90s, and I was watching the news. This was before social media; it was still very traditional: radio, TV, cable news. I was looking at the news, and I realized that the students at the school were never asked, “Why do you think this happened?” Rather, it was the media talking or others who were asked, and they were like, “Well, this is the problem. It’s too many guns, or it’s video games.” And I thought, “Wow, what are the students thinking?” They’re the ones that are experiencing this— their peers are the ones who took up the guns and began shooting. So I realized in that case, I could create a project where we brought in teenagers, partnered them with artists, and had them create some kind of work where they tell their story and express why they think this is happening. It became a media project: videos, billboards, photographs, and exhibitions. They did a radio show—I started it in San Francisco, and then I went to Los Angeles, DC, and Chicago. I can remember walking down the street—back then, we had those metal newspaper stands—and there it was on the front page of the newspaper. I saw the billboards that everyone had created, and then it was on NBC Nightly News with Tom Brokaw. So, it became national and gained a lot of media exposure. At the same time, we had gun violence prevention classes and a peace parade, where tens of thousands of people marched through Chicago with homemade peace signs. It ended in a festival where we had a barbecue and kids’ games, and a street festival. A lot of the people who participated in the project were able to go on to launch careers or take that work and do other things.

Often, [my projects are] inspired by what is going on politically in the moment. But, I’ve turned certain things down because not every political cause is a connecting point for me or somewhere where I can see myself truly having some sort of impact.

What project are you most proud of throughout your career? Have you had an experience where you felt like your art tangibly impacted a community or sparked needed dialogue?

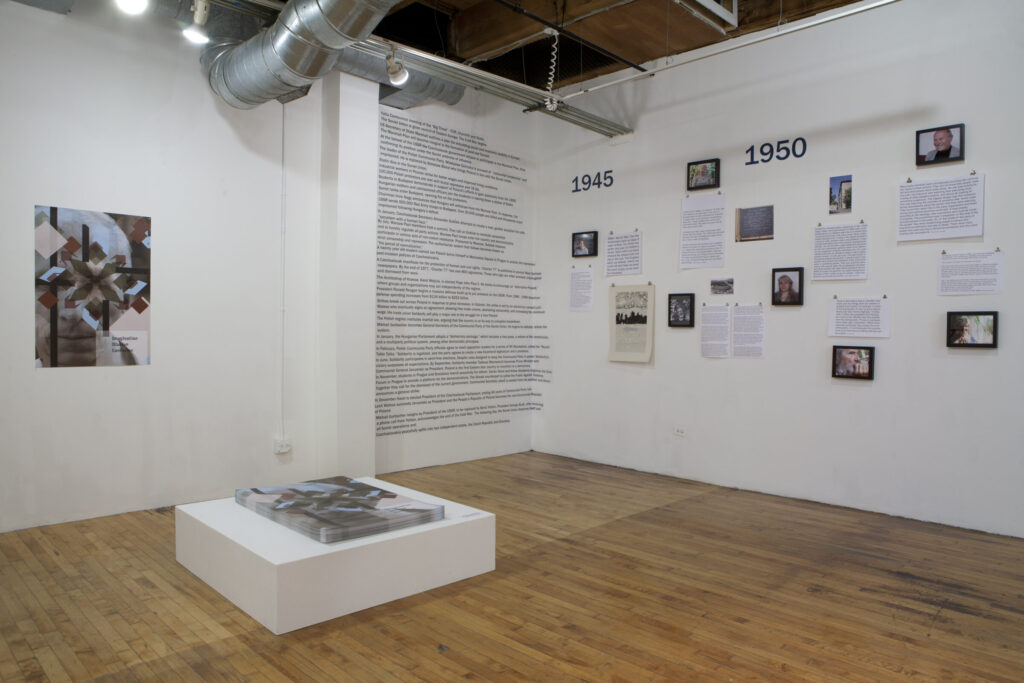

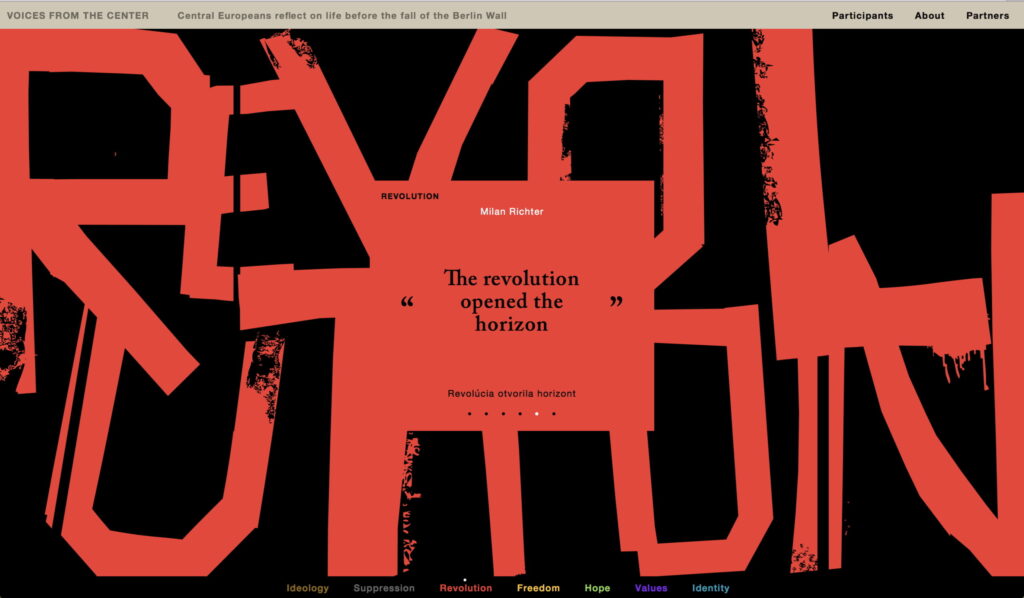

Projects that stand out for me include Voices from the Center—it’s an oral history project I did in Central Europe. I was on a Fulbright scholarship, teaching a class at the Academy of Fine Arts and Design, about how to produce a social practice-based arts management, the real technical aspects of doing this kind of work. The course had its own interesting political output from the students. I had both graduate and undergraduate students, and they were creating very big projects in the city of Bratislava. At the same time, I was talking to my peers, my neighbors, and my new friends about growing up during the Cold War—about what it was like on the other side of the wall because on both sides, there was propaganda about the other. After hearing those stories, I started to diary them, and the project started to grow. That’s how a project can grow organically. Over time, I ended up expanding this project to three other countries in the region, known as the Visegrad countries: Poland, Hungary, and Czechoslovakia (now the Czech Republic and Slovakia). Because they had different flavors of communism or socialism, the stories were different and reflected the impact of the regime that was ruling in those countries.

It had an impact, because I was told by people there that it would take an American or someone from the outside to do this. This is something I’m very conscious of when I’m working: to be really careful with the role of the insider and the outsider. In this case, being from the outside granted me a sort of movement as an educated outsider—an outsider who attempted to speak all the languages, even though I always had a translator with me, as I started to not just talk to friends, but make appointments. There was real value in that. Then, that project went on to be an education program in schools, in colleges, in K-12s, and came to the States. It’s been exhibited throughout the States. I’ve gone back and re-interviewed people 10 years later about how their lives are now, 25 years after the wall fell. It’s really instructive, actually, for our current political moment, especially with the conflict in Ukraine. I also brought in a lot of other artists when the project expanded and helped to create platforms for their work to tell these stories.

Is political meaning in art always intentional?

No, because interpretation is subjective. The viewer brings their politics to the art, and then it might become political. Some people view other things through political lenses all the time; other people don’t have a political bone in their body, and context matters. Art doesn’t exist in a vacuum, so the cultural moment can influence how we might view or experience art.

For you, is the art and the meaning that comes with it integrated? Are you ever making art just to make art, or, for you, is making art centered around being able to spread these messages that you’re passionate about?

That’s changed, and still changing. When I was living in New York, I was working in art and activism as a volunteer. I had my day job as a photo editor, and, as a young artist in New York, I was making work and starting to exhibit it in museums and galleries. That was going well, but it was the political activism where my heart started to sing, [especially] when I saw the impact that the work I was doing was having with people. At one point, I started doing less studio-based work and more project-based work that’s very collaborative, much more my vision, and very process-oriented. When doing this work, you need to be open and listen to the community and the people you’re working with—and that is process—and then the project changes and grows depending on their expertise, knowledge, and what they’re bringing to the project. Now, I have started to go back into the studio a little bit and work on multimedia pieces. That’s something that I’m doing again, because I’ve come to a place where there are things I want to explore, express, and discover that I can only do with my hands in my own work.

What do you consider to be the role of the artist during times of political uncertainty?

I don’t believe the artist has a role per se. There are artists who engage politically through their art and throughout their careers, and there are artists who are called to political action during times of political uncertainty, and that could be through art making or contributing to politics and society through their actions outside of their art-making, such as protesting and volunteering. And then there are those whose art becomes political in the moment, who all of a sudden realize [their power]. I think, certainly we saw that in the middle of the last century with the rise of fascism and during World War II, when many non-political artists became political. So, I think it’s very individual, and that the artist doesn’t have to play a role, but I sure admire the heck out of those who do.

Does an artist have a distinct responsibility in activism, or is that responsibility the same for every community member?

I think ideally every community member should be active. I was talking to someone, who is the CFO of a pretty big company the other day, and they said, “What are you doing the rest of the day?” I said, “We’re going to the “No Kings” march.” And they said, “What’s that?” This really showed me just how out of it people can be—how non-political or non-engaged, and why we’re in the place we are right now in this country. To me, it’s really sad that people are so detached from what is happening—even someone who’s intelligent and holds a position of power and responsibility in the business world. It would be a utopia if, in all political persuasions, we could come together as activists and start to work together. Maybe we’d evolve a little bit as humans.