Jody Quon, born in Montreal, Canada, in 1966, studied art and fashion at the Rhode Island School of Design before transitioning to the worlds of photography and journalism. She began at The New York Times Magazine as a photo researcher and became Deputy Photo Editor, working under their renowned photography director, Kathy Ryan. In 2004, she joined New York Magazine as Photo Director. During her time there, she won numerous awards, including the National Magazine Award for photography, a Robert F. Kennedy Journalism Award, and a George Polk Award, and in 2025 she became the magazine’s Creative Director.

What sparked your interest in the arts and how did that lead to your transition from fashion to photo direction?

Since I was in high school, I’ve loved art. On Saturdays, I used to take the metro from the suburban town where I lived to downtown Montreal, and I would typically go to the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts and a slew of interesting galleries on Crescent Street.

I went to art school and I studied fashion design, but my interests were always in the intersection of art and fashion. When I graduated from college, I realized I was never going to be as good a designer as the designers that I really respected. I worked for Rei Kawakubo, [a Japanese fashion designer], doing fashion research for five years. After those five years, I felt that I had served my time.

I thought it could be interesting to work at The Costume Institute at the Metropolitan Museum of Art (The MET), so I reached out to the co-curators there, with whom I had built a relationship with, but they told me that to work at the MET, I needed a master’s degree. They were at a dinner with Carrie Donovan, the fashion editor for The New York Times Magazine at the time, and Carrie needed a young photo researcher to help her with digging up a lot of the old photographs that were made for the fashion supplement of The New York Times Magazine to celebrate its 50th anniversary, so they referred me to her.

I worked for six months on this project, and met with Kathy Ryan every Friday for her to edit the research. We developed this rapport, so when I finished my six months of the research project, she asked me if I would be interested in joining her department as a junior photo editor.

When I was working for Kathy, I didn’t mind not working in fashion anymore. I loved working in real time on real stories that were going to make an impact. I felt like every day I was going to school with the most brilliant people on the planet, because you have all these brilliant editors working with brilliant writers on the most important stories about what’s happening right now in our world and our culture.

On the one hand, we’re doing a cover story on Bill Clinton, who was the president at the time. On the other hand, we’re doing a story on Bruce Springsteen or Stevie Wonder or on risotto being the food of the moment. It was all over the place, but so fantastic. We always asked, “What are the stories we can tell that say something about who we are right now across all disciplines—politics, business, art, culture, movies, and television? What is happening and what does it say about who we are as a people?” That’s what I’m interested in. It took me many years to figure that out.

I joined New York Magazine in 2004 to become the photo director. I worked there from 2004 to 2010, and left in 2010 to become creative director of W Magazine. I realized W Magazine was not the right fit for me, and then I came back to New York Magazine in the spring of 2011. It was when I returned that I realized my heart was not actually in fashion, or even in fashion photography. My heart is in news and journalism in general—telling stories about who we are.

Which story are you most proud of working on throughout your career?

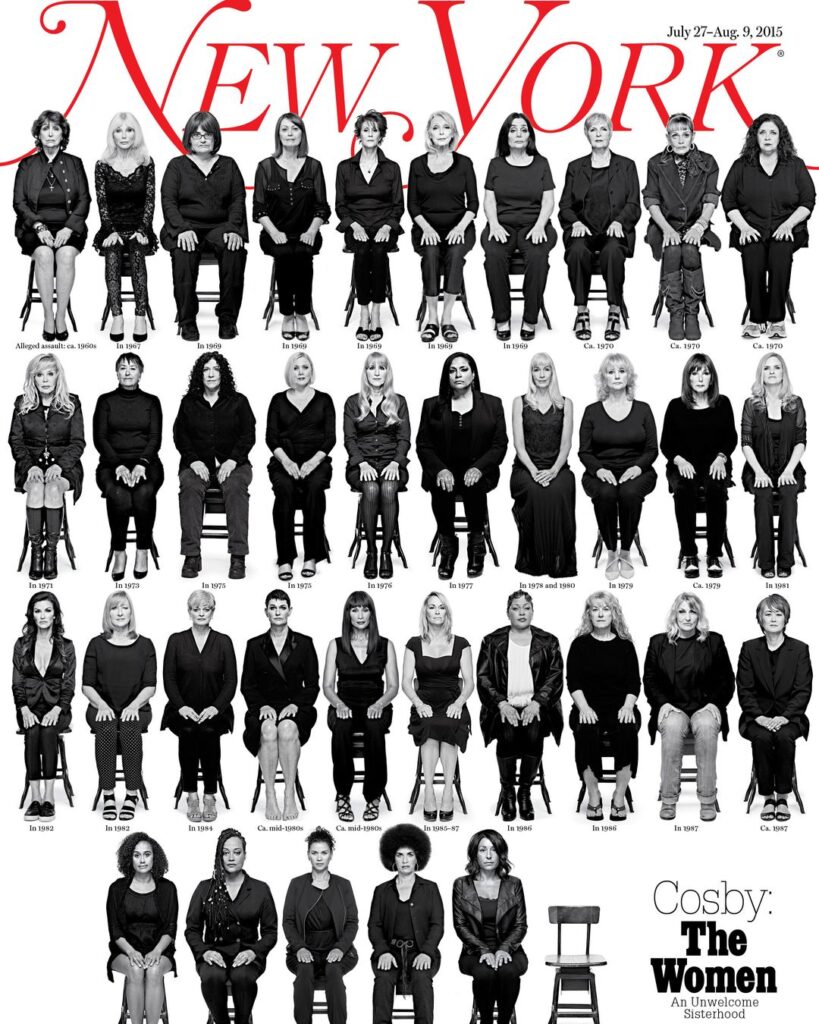

I’m proud of many stories. I’m in a privileged place where there are so many important stories to tell, and we can recognize them and dive into them. The Cosby story was really important. It was a hunch that I had when women were starting to come forward about their alleged sexual assaults by Bill Cosby, while traditional and more serious news outlets were not paying attention to those stories. The only people who were listening were publications like E! Entertainment, Entertainment Tonight, or lower-tier celebrity publications.

There were maybe eight women who I was seeing telling their stories on these news outlets. I brought the idea to my editor-in-chief in January of 2015. I said, “I feel like there’s a story to tell with these women who are accusing Bill Cosby of sexual assault.” And my editor said to me, “There’s no story if you don’t get Bill Cosby.” I disagreed. I told him that these women were all telling a similar story and that we needed to listen to that, and there were so many of them. I gathered the information properly and made a presentation. I gathered as many names as I could. I figured out their ages, when they were allegedly assaulted, and where they lived in the United States.

I came up with over 20 names, just for the initial meeting. Their ages ranged from 27 to 80. I said, “There’s a pattern here. We can’t ignore this.” He asked me to get a read from other people on the staff. I go to the managing editor. She’s like, “Isn’t it a little bit exploitative if we do this?” I said, “I don’t think so.” As a mother, if one of those women were my daughter, I would want that story to come forward. We need to make this story public so that it doesn’t happen to the next woman.

Finally, my boss said, “Let’s do it, but you can’t spend a lot of money on this. Maybe at most, we’ll give it four pages in the magazine. Make sure you shoot it so you can run it in a compact way.”

The first photographer I went to was a male photographer. He told me he was not sure he saw the potential of the pictures. Then, a light bulb went off in my head. A woman needs to shoot this story, and it needs to be a woman who is of a certain age so that these women [allegedly assaulted by Cosby] feel comfortable around her. That’s when I assigned it to Amanda Demme, and we shot it in three different cities. We wanted the photos to be as elastic as possible, so we decided that we would photograph the women in the studio and they would all wear white, so that we could focus on them as opposed to their fashion choices. We shot them all in pairs, but there was an odd number of people in different cities, so sometimes only one is sitting on the chair, and there’s an empty chair next to them. The empty chair symbolized all the other women who hadn’t come forward, because there were many more than just the ones that we photographed.

We ended up putting it on the cover because, all of a sudden, Cosby was in the news again, before one of the depositions was happening. It became a huge thing even before the MeToo movement. This predated the MeToo movement. The cover went viral worldwide. It became one of our biggest stories ever.

That story is important because it was something where I had a hunch, and my hunch paid off. Once my editor decided that we should go all in, we had the reporter interview all the women. We did videos of some of the women telling their stories. It changed the conversation. It was the first time that we were able to take down such a famous person, someone who was like America’s father.

Frankly, the Harvey Weinstein story that the New Yorker did and that the New York Times broke couldn’t really have been achieved if the Cosby story hadn’t been done. There’s a kind of trickle-down effect that happens.

As a photo director, what do you think of the relationship between the photographs and the written text? Is one medium more effective for political expression than the other?

We make a magazine, and the magazine has words and it has pictures. The pictures make the words better, and the words make the pictures better, and they work with each other—that’s what makes an extraordinary magazine. It’s all about context. You need the two to get the reader to pay attention. The visuals team has a very close working relationship with the editors and the writers, as everything has to click together.

It’s all about the language that you put next to an image. For example, you have an artist like Barbara Kruger, who did one of our most iconic covers, the Eliot Spitzer cover. Eliot Spitzer was the governor of New York from 2007 to 2008. We published this cover of him after it came out that he was involved in a high-end prostitution scandal and was forced to resign. I called Barbara Kruger and asked, “What is your reaction to this?” I sent her a picture of Spitzer, and then she sent me back [that picture with] the word “brain” pointing towards his penis. The picture is nothing without the language. That’s an extreme case, but they work together, hand-in-hand.

What is the responsibility of people working in magazines and other storytellers to speak on major but sometimes controversial political issues and tell those stories properly?

Huge—and we don’t take it lightly. We always try to be as thoughtful and considerate as possible. We talk about being neutral all the time. We did “Crimes of the Century,” a cover story in June on the Israeli government’s attacks on Gaza and how they would be tried in an international tribunal, and what constitutes a war crime. We were very careful about the kind of imagery we were using, so that anybody looking at these pictures could not accuse us of taking one side or another.

What was it like to collaborate with a student newspaper during the Palestine Protests at Columbia University?

We were working with the editors, writers, photographers, and photo editors of the Columbia Spectator to report on what was happening on campus at that very fraught time in the spring of 2024. We tried to be very neutral. It was interesting, because I was working with the acting photo editor of the Columbia Spectator, because the original photo editor had decided to recuse themselves from reporting on what was happening on campus altogether, because they didn’t feel comfortable. It was a really thrilling project for me to work on professionally. I basically worked out of the Columbia campus for a week straight because I decided immediately that I couldn’t do my job properly sitting at my desk in my office; I needed to see what was happening for myself. I was going to campus every day, working with the photo editors and the photographers directly on hand to figure out how to tell that story. I felt that the outside press wasn’t getting the story right because they weren’t allowed onto campus. The world at large didn’t see what was going on on campus, and it was very different from what people were reporting. I think that we reported something very fair: just purely reporting what was happening on the ground. I’m sure that we probably alienated some readers, but I think people generally felt that we handled that fairly.

Do you ever want to make a more subjective argument but feel prevented from doing so by the responsibilities of a magazine?

No, as a journalist, I have to put my personal issues aside. Objectivity is the most important thing; our objective is to tell our stories fairly. I think it’s important to share different points of view, but you have to tell them fairly and within the right context. I’m editing stories all the time where I don’t necessarily agree with one’s point of view, but I ask myself, “Do I agree that the story is being told fairly? Do I believe that the accompanying photography or art treatment is correct and appropriate?” It’s all about separating your personal feelings and making sure that you’re doing justice to the story.

How do you choose which stories to tell?

We’re not going to tell the daily breaking news story, because that’s not our lane. Leave that to the New York Times. We’re constantly trying to figure out what the story is that we can tell about a national issue that has its own personality and contains that “nugget” in there that feels very us. We only have so many stories we can tell, and it’s up to the editor-in-chief to figure out what stories in a given year will best express a point of view about what happened that year and about where our culture is right now.

We ask ourselves, “How do we tell the story about the crisis in the Middle East right now?” It’s being told in so many different ways. We have to figure out, “What is our special nugget in this crisis where we have something new to tell that’s going to add to the conversation?”

We don’t just want to report the same thing over and over again. In the case of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, that’s why we did that cover story on war crimes. We got Suzy Hansen, this very scholarly writer, to do an incredible analysis and figure this whole thing out, to make people read and stop. That’s what we’re always trying to figure out—what is the singular idea within the whole bigger picture, where we have something new to tell.

Are magazines past their prime? How has the rise in technology and polarized media changed the industry?

I don’t think so. I think that there’s still room for what magazines do—they give you distance from a story. Jeffrey Epstein goes to jail, and the newspapers are going to report that instantly. Bloggers are going to write something online. But, there is something special about the packaging of stories in long-form journalism, where you have a writer who spends three months researching an article, interviewing people, formulating a story, and then figuring out the accompanying photography. A reader can really digest it. They can read a cover story, turn the page, read it at their leisure, look at the photographs, put it down, and pick it up again. I think that people will always enjoy that.

We have a very strong print readership; people still love getting our magazine in the mail. Are people consuming a ton of news online? Yes—but people still have a thirst for old school, thoughtful, in-depth journalism with beautiful sentences and packaging. The elegance and the rhythm of turning pages is very different than when you’re scrolling on your phone. If this is how we’re going to be reduced to consuming news, fine, but that’s not what we’re doing. We’re not delivering news. We’re delivering feature stories that people have crafted. People have considered the paper, the typography, the photograph, and the layouts.

The level of work that goes into all of our stories is so that we can deliver something special to the reader, and I think that readers will always have an appetite for that. There are not a lot of magazines out there because they’re very expensive to produce. So, the playing field is much smaller. I think that there will always be a market for the magazine.