Platon is one of the world’s most celebrated photographers, renowned for his portraits of world leaders such as Vladimir Putin, Donald Trump, Barack Obama, Muammar al-Qaddafi, and Bill Clinton, as well as iconic cultural figures including Muhammad Ali, Edward Snowden, and Stephen Hawking. Beyond capturing the powerful, Platon has dedicated himself to amplifying the voices of those fighting for civil and human rights through his non-profit organization, the People’s Portfolio. This work culminated in his 2024 collection, The Defenders: Heroes of the Global Fight for Human Rights, which spans 15 years of documenting human rights activists around the world. Having shaken hands with more of the world’s most powerful leaders than perhaps anyone else, Platon offers a rare perspective on power—from those who wield political and financial influence to the everyday heroes whose courage shapes the world.

This is the extended version of an interview that appeared in Issue I (2025). It has been edited and condensed for clarity.

All photos courtesy of Platon. Featured photo by Mike Foley.

You’ve photographed Trump multiple times—how does he wield media and public attention to assert power?

A few days after Trump had won the 2024 election, I was waiting for him to appear at Mar-a-Lago to do his portrait for Time Person of the Year. He was literally forming his cabinet around us that day and was called away to an emergency meeting about tariffs.

Nearby, all the editors of Time were also waiting to interview him after my photo shoot. As I waited, I started talking to one of them. He laughed, saying that Trump’s first cover was fake—he had made it himself and hung it in his Trump Tower office. Soon, all the journalists were laughing at the idea that Trump had faked his own Time cover.

So that’s kind of funny, but think again—he’s a man who has a vision and will do anything he can to make that vision come true. He sees himself on the cover of Time, even if he’s not, and the vision is so strong he makes a pretend dummy of it himself and puts it on the wall for others to see.

And now, as all the editors were laughing at the fact the first one was fake, I said, “Yeah, that may have been fake then, but it’s not fake now, is it?”

He’s just acquired the position of being the most powerful man in the world. He beat all his political opponents. He’s got dominance over the Supreme Court. He’s got the Senate. He’s got Congress. He won all seven swing states in America. And he’s nearly had more Time covers than anyone in history. You guys gave him that. So, I don’t know why you’re all laughing, because if there’s a battle between you journalists and Trump, it seems pretty clear that Trump is victorious.

There’s this wood-paneled room in Mar-a-Lago that’s used all the time for press. When you walk in, there’s this portrait of Trump on the wall in the 1980s. He’s wearing a tennis sweater, and he looks very regal. Very handsome! Underneath the picture, it says, “Donald Trump, The Visionary.”

It’s all there, man, it’s all there. And so many people in the media missed it. They were distracted by the chaos, and the jokes, and the crazy behavior. And while Trump gave them all that to chew on, he just plodded along and made things happen.

So, while I was waiting—and it was a long meeting, three or four hours—his team was playing me music.

Before a shoot, I have to empty my brain so that when the person walks in, I can concentrate 100% on who they are. It doesn’t matter what my agenda is. In fact, I must not have an agenda. I have to strip myself so bare that all my attention and senses are consumed by that person’s presence. Only then will I see, catch, and capture the little details that most people might not always see. It takes a very high level of concentration.

With that said, I’m going into this state of hyper-observation and concentration, when they decide to start playing music. Normally, when you’re in an elevator or supermarket, you hear the music but you’re not really listening.

But in my state of hyper alert, every single detail around me is magnified 100%. All of a sudden, these songs go into my brain. They’re all very famous. I know almost all the words to all the songs.

I thought, “Wow, this is very odd. The new president is playing me pop songs.” You would think they’d be playing Beethoven. Who chose these, and why did they choose them?

Eventually, he walks in. We spent a few minutes talking about how our lives have changed since we last met 22 years ago. A lot has happened to me, a lot has happened to him.

Then I said, “Mr President, I’d like to ask you about the music I’ve been listening to.”

He said, “Oh, that’s my personal playlist. I asked them to play it for you.”

I said, “It’s very long—I’ve been here four hours without a repeat.”

He said, “There are 2,000 songs on it. I chose each one very carefully. Each tells a story, my story.”

Then I realized it all made sense. He’s working with material you already know, so you don’t have to work too hard to listen to the message. What he’s doing is harnessing that message, twisting it, changing its meaning, and giving it back to you. He’s mobilizing popular culture and sending it into battle.

I discovered afterwards that he played that playlist at his rallies, to hundreds of thousands of people. I presume he plays it to all the politicians and world leaders while they’re in the waiting room to meet him.

Now, what are the songs? We Are the Champions, by Queen. The Winner Takes It All, ABBA. My Way, Frank Sinatra. Nothing Compares 2 U, Sinéad O’Connor. Suspicious Minds, Elvis. Nobody Does It Better, Carly Simon.

Now you start to see what he’s doing. I’ve never met another politician in my life who spends their valuable time making a playlist to play to people before they meet him. Nowyou start to see what he’s doing. He’s creating a narrative. Creating a mood. So, when you meet him, the story has already been told.

In every one of my pictures, he has his hands on his leg, and one hand covering the other. You’ll see it if you look at my Time cover. At one point, I noticed his hand slipped, and there was this dark mark there.

“What’s that on your hand?”, I said. He showed me, and he had a big bruise.

I said, “Wow, what happened? Did you hurt yourself?”

He said, “No, it’s from shaking thousands of people’s hands during the campaign.”

I realized people aren’t just politely shaking his hand; they’re grabbing it. There’s passion. They’re pulling it.

Now, Biden, I don’t know how many hands he shook. I don’t think he did many rallies. Trump did a hundred rallies. Whether we agree with his politics or not, that guy was the hardest-working man in show business and politics combined.

Biden was heavily protected. They wouldn’t let him see anyone or sit for me, even when I invited him. There was a smoke screen, and you couldn’t get to him. In politics today, as I said at the beginning, all you need is attention, and if you’re not getting it, the game is over. Trump knows this better than anyone.

Trump is interesting to me because everyone underestimates him. They write him off as a clown and assume he’s not intelligent. I would argue that he’s one of the most cunning, clever world leaders I’ve ever met.

Every world leader I’ve worked with has used their personality, past, and human experiences to chart their style of power. Each power play comes from their makeup, their DNA. This becomes their actions, then their legacy.

Someone like Obama doesn’t like conflict. He will do whatever he can to transform discord into harmony. Not because he’s doing everyone a favour, but because he’s creating the terrain where he can thrive and be at his best.

Trump is in tune with something different. Most politicians think that their qualifications to become a power player are to have gone to Yale, Harvard or one of the most incredible universities in the world, and then to work their way up through an established system.

For Trump, you could say his biggest qualification was having had his own reality TV show. Now we can laugh at that—it is kind of funny—others may say it’s terrifying.

A reality TV show’s success is built on ratings: if they’re bad, the show is cancelled; if good, it goes on. He has turned politics into a game of ratings, which really, it always was—votes being ratings. It just so happens that Trump’s qualifications—capturing your attention and holding it––is currently the biggest social currency there is. That’s why he’s always talking about ratings and audience size. That’s his metric system.

His goal was to connect with people, communicate with them, inspire them, capture their attention, and bring them on board. He sees that if you can win people over, you can exercise power.

He also sees that the way we now communicate is changing fast, but the idea of politics hasn’t adapted quickly enough to the way we have changed. So, politics starts to feel outdated. Laws and constitutions never seem to change and if they do, it is very, very slowly.

Now compare that with the development of communication. It has skyrocketed with social media and AI. It just so happens that Trump’s qualifications––capturing your attention and holding it––is currently the biggest social currency there is. That’s why he’s always talking about ratings and how big the audience is. That’s his metric system.

Trump understands that whether there is conflict or harmony, the most important thing is attention. In 1967, John Lennon said, ‘All You Need Is Love’. If Donald Trump made a statement today, it would be, ‘All You Need Is Attention’. That’s the most valuable thing now. Everything has shifted.

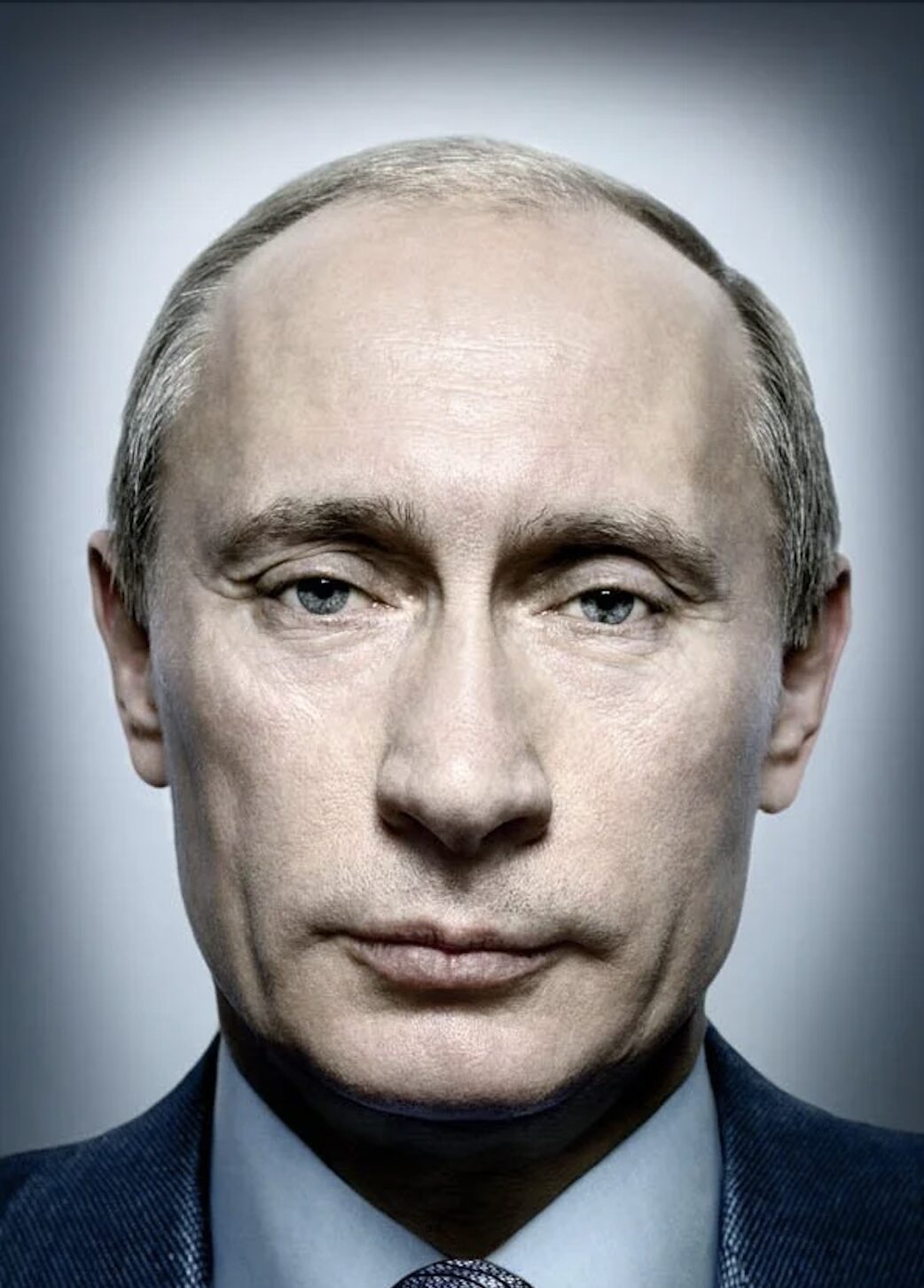

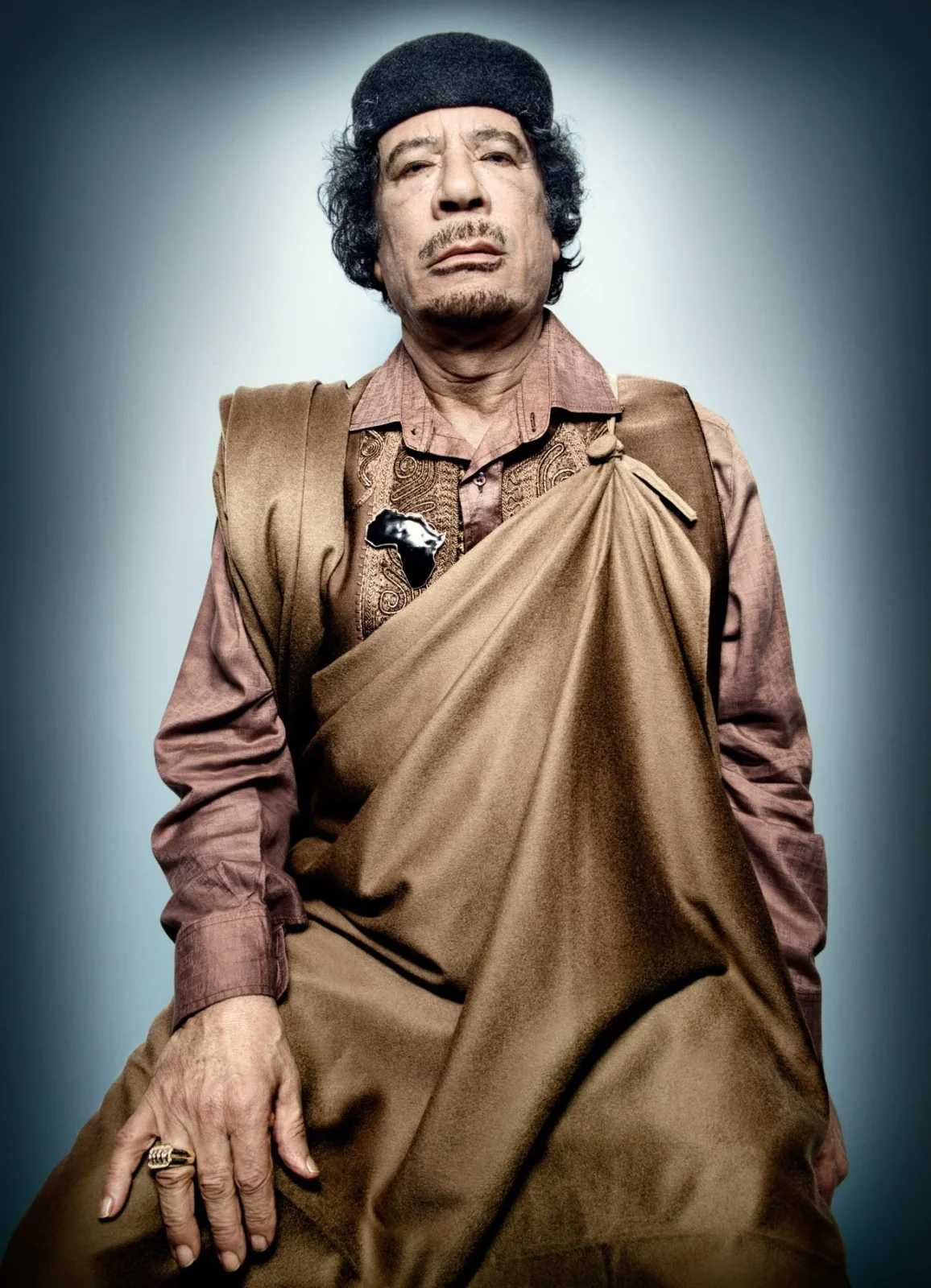

What goes through your mind as you prepare to face someone like Putin or Gaddafi for the first time?

Now, when I look back, I don’t know how much danger there really was. At the time, it’s quite frightening. Then, you start to realize that this is the game, the theatre of exercising power.

Every administration around the world does it in a slightly different way, whether cultural or based on that leader’s demeanour. It starts with the leader’s personality. Then there’s this ripple effect around them of what that atmosphere is going to be like. Is it going to be more about intimidation, strong authority, charisma, stateliness?

Putin was the first time I had been exposed to this kind of thing, so I didn’t fully understand that this was how the system was built. I was really nervous. I couldn’t believe I was in the room with him.

Then, little by little, he gradually got closer and closer to me, to the point where I’m just a couple of inches away from his nose, and then we’re talking about the Beatles.

Power is a really interesting dynamic. We all use it. Think about your family or group of friends, if I asked who the most dominant person is, they would probably become pretty clear, pretty quickly.

There are mannerisms we do. They might not laugh as much at a joke. They hold back, make you work harder. The worst bit is as soon as you sense this, you find yourself working harder. Then they’re rewarded, the cycle repeats, and before you know it, the dynamic of dominant to sub-dominant is extreme.

Now, magnify that a million times when it comes to politics or business, and this thing gets out of control. That’s what I’m up against.

So, when you have someone that’s dominant, they’re not dominant from the beginning. With Putin’s style of power, it’s a dynamic with sub-dominant people that’s gradually magnified. We all play a role in this power game. If the person who is sub-dominant stops playing the game, then the person who’s dominant loses their power.

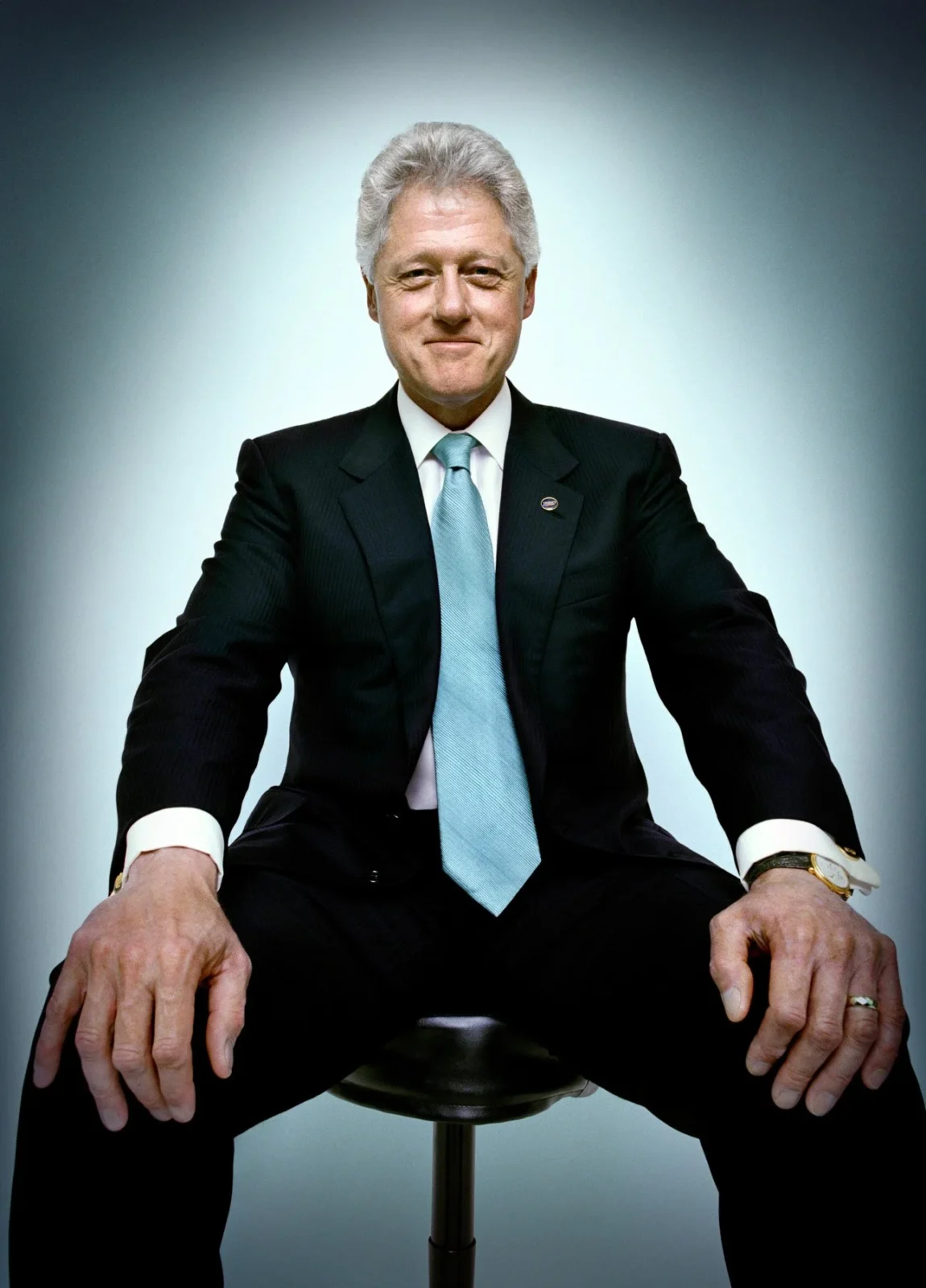

I’ve learned that because I don’t want any of their power, the power dynamic doesn’t work on me. I don’t want their political power; I wouldn’t know what to do with it. If I’m working with someone very wealthy, like Bill Gates, I don’t want their money, and I certainly don’t want their fame. I’m immune.

What I really want is an important picture, and if they’re prepared to give me that, then that’s our currency. We have to collaborate to make something that’s meaningful, that stimulates respectful debate. If I can do that, then I’ll work hard to get that. But from them, personally, I want nothing, which means their power is meaningless to me. That makes a great leveller.

So if you suddenly say, I’m not going to reward you for being powerful, then they’ve just lost their power. I feel in those circumstances that I am not impressed by their position. They know it. They feel it. We’re all intuitive as human beings. And the strange thing is, a lot of the time, they give me respect, because we’re now equals again.

That allows me to have a different type of conversation with people, and it’s not a disrespectful conversation. I always respect their responsibility, but this idea that they are supreme is nonsense; it’s an illusion, and they know it’s an illusion. If we both have that understanding, then we can be equals, together, and collaborate.

That doesn’t mean I’m promoting them. There’s a big difference between an artist and a promoter, and I’m an artist. But my role is to create something that will stimulate debate, a respectful debate, and help people understand things a little more.

Some people said to me, “You made Trump look too good.’ I didn’t make Trump look anything. If that angers certain people, then that’s interesting. And some people will say, “You didn’t make him look good enough.” We hold a mirror up to society.

What we can’t doubt is that he is now the most powerful man in the world. He holds ultimate power. The day I photographed him, he was at peace with himself because he got what he wanted. So that was reflected in my picture.

How do you capture world leaders in a way that reflects both their power and its consequences?

When I was at the UN General Assembly in New York, I built a photo study to photograph world leaders. It took 67 meetings with the UN to win them over and let me in. When I began, I had no prior permission from any subject to sit for me; you couldn’t negotiate that in advance.

Once I was in, it was like a street hustle. You go up to a head of state and say, “Excuse me, can I take a picture?” Initially, I had no one sitting for me, but then you get one, and then you get two, and before you know it, momentum starts to build, and it turns into a private club that they want to be in.

It turns into, “Oh, there’s this guy taking pictures of the world leaders, we should do that.” Soon enough, people were coming up to me saying, “Excuse me, but our leader has not been invited. Can we pencil in a time tomorrow?” My assistant would be saying, “President of certain country, sure we can fit you in at 3:30. We’re a bit busy before.” It was insane.

At other points, they all came in clusters. I would have ten of them in line waiting to have their picture taken, like they would at school. And of course, while they’re all waiting, they’re having a conversation. It turned into an event.

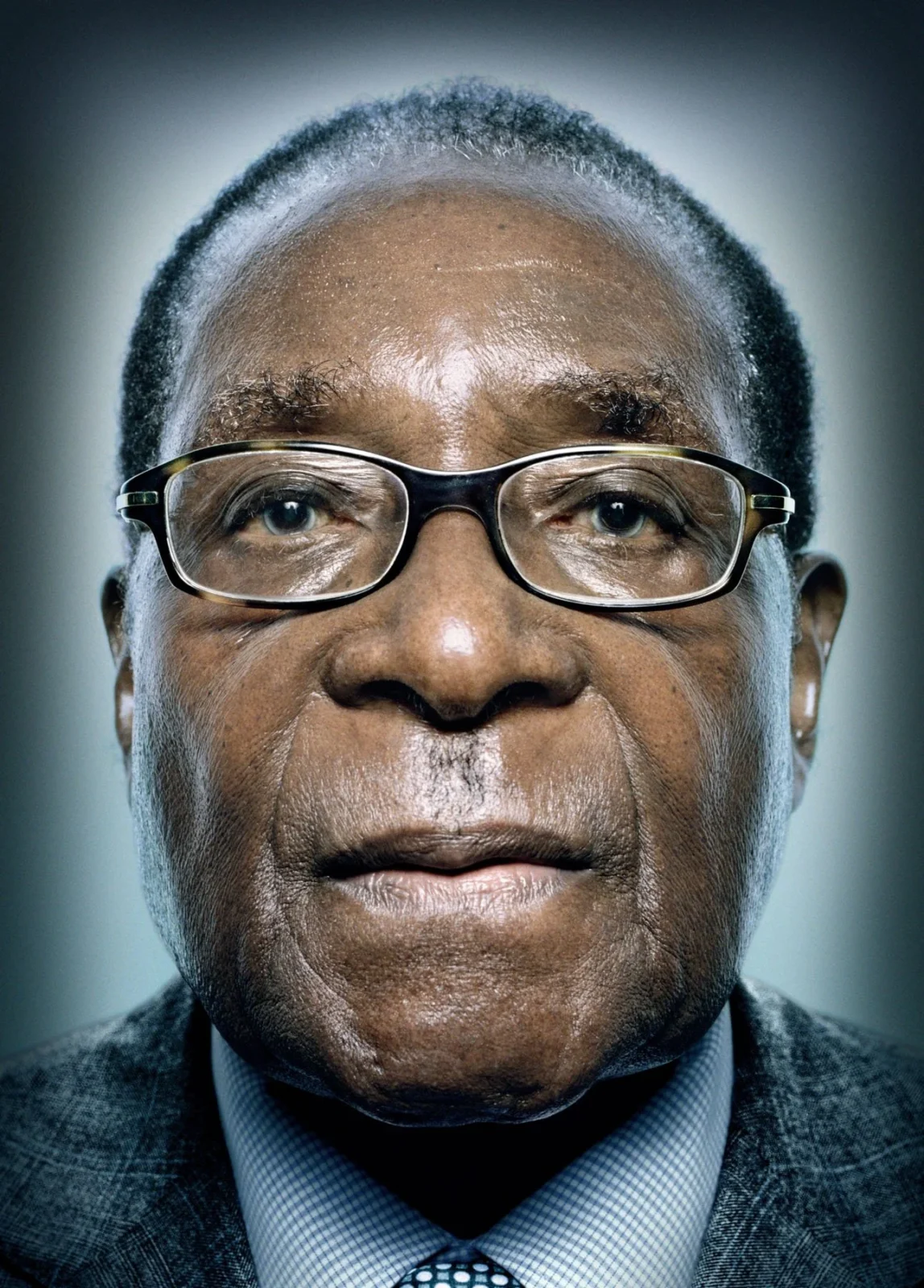

At one point, Mugabe came to sit for me. He walked in. He was very gentlemanly, very polite, but gave nothing away. He sat down. He was dapper, well put together, with a perfectly done tie. Everything was symmetrical. I take a picture, and it’s like ice.

I looked into his eyes, and they were a crystally blue. It was like this ice soul frozen over. His skin was almost stretched over his face. It almost looked like glass. He stood up, walked away.

I have this little wooden apple box that everyone sits on. It started off as something anti-fame and power—it’s not a throne or a glamorous chair, it’s just a box. But over time, even the box has become famous because of who sat on it. I’ve been told more world leaders have now sat on that box than on any chair in history.

So, Mugabe walks away, and then another head of state comes to sit down, and he sees him walking away.

I said, “Would you like to sit on the box?”

He said, “I will sit for a portrait, but not on that box. There’s blood on it.” That was a chilling moment.

Photographing world leaders is incredibly sensitive work. When I’m taking pictures, I’m in a different place—focused on their body language, aware of every detail. I tell my assistants, when they’re doing light readings, they can’t come in directly because the Secret Service won’t allow it——they’ll arrest you straight away. You have to come in gently, gesture that you’re doing a light reading, and then move out sideways.

Some of these world leaders, you’re not even allowed to touch. You have to be physically and emotionally aware of every move—no sudden movements. It’s even more sensitive when we’re photographing human rights victims, especially someone who’s been hurt, tortured, or traumatized. So that’s where my head is usually at. It’s not in the broader context at that moment. That was a wake-up call.

“Snap out of it, man, you’ve got to remember that these guys can be responsible for so much trauma in society,” I often feel that after I’ve finished the picture.

I put it back into society for debate, and then I see how people respond to it.

Have you ever noticed and captured something unexpected in a world leader?

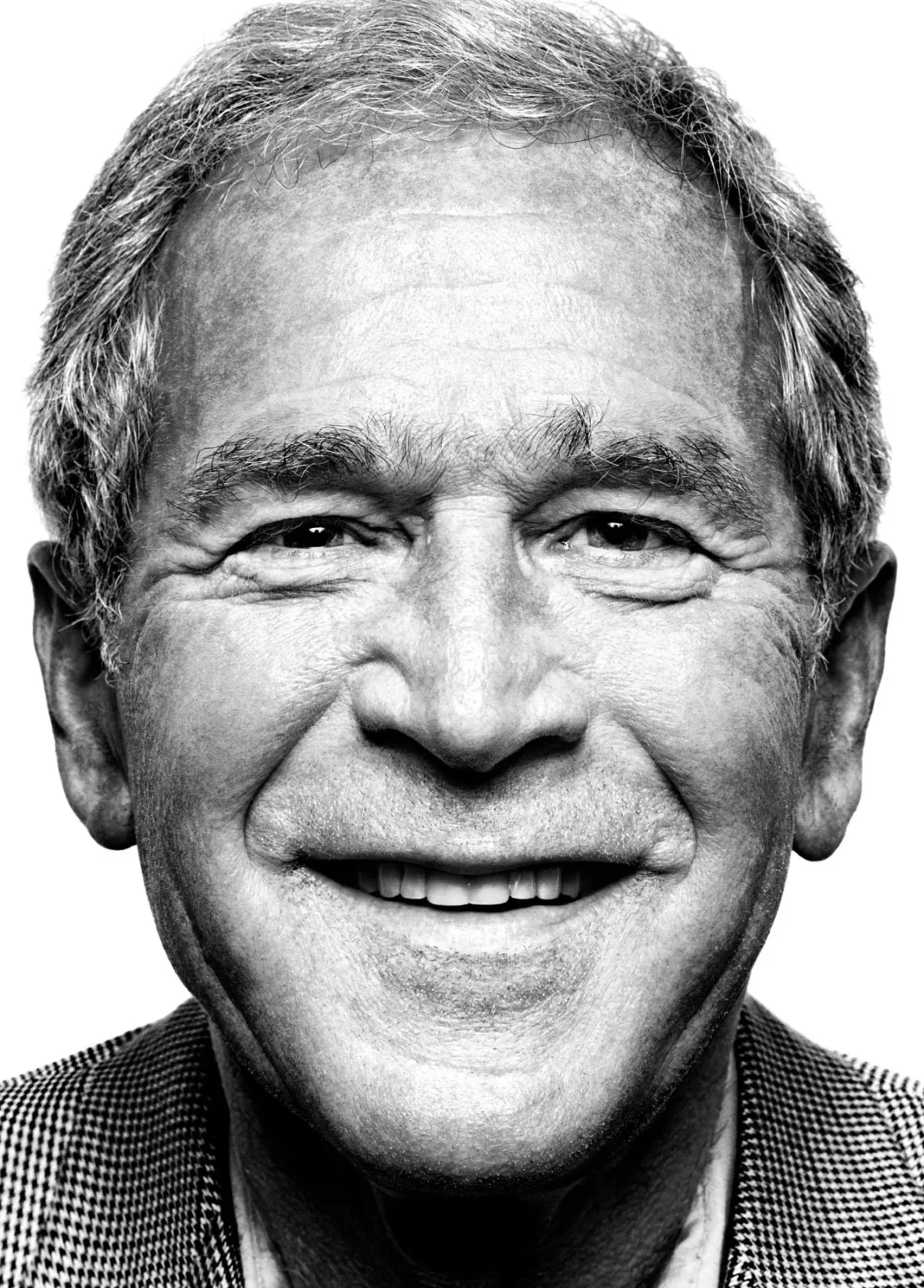

That happens a lot. W. Bush was almost aggressive to me the first moment I met him. He had just left office when we got the picture. Now, put that in context. He had been in office for eight years. We’d had 9/11, Afghanistan, and then Iraq. Then, just as he’s getting ready to leave office, we have an economic meltdown. It really felt like the world was in chaos.

At the same time, you’ve got Obama rising, a black man, breaking barriers in society, referencing Martin Luther King’s dream, and seen as a political Messiah. Obama won, and there was jubilation around the whole world. I was just wondering, “What is he feeling at that moment?” He must have been thinking, “I’m just glad this is over. I’m out.” Now that he’s left office, he has time to reflect. You don’t have that time for that when you’re running a country.

It’s like me taking pictures. I’m not reflecting on them when I’m taking them; I’m completely consumed. It’s only after you’ve finished that you look back and say, “Was that good? Was that bad? How did I do? Was I successful, or did I fail?” And I’m sure he was going through a bit of that. He must have been, especially seeing the whole world celebrate, not just that Obama’s arrived, but that W is gone.

And so, the last thing he wants is to be photographed in that moment of vulnerability, especially with my kind of approach where I’m really focusing on his humanity in details. So, in every single picture that I take of him, he puts on a mask, and he smiles in every shot.

Of course, you think of Iraq, you think of the chaos the world was in, and the economic crisis that we were all facing, and he’s smiling. Perhaps he’s trying to put on a show that he’s not vulnerable at that moment. But if you think about it, the message he was trying to send out was also quite inappropriate. He’s smiling, considering the state of the world, that’s kind of crazy. All these interpretations went through my mind afterward.

After a few years, not that long ago, I got to know Condoleezza Rice really well. She’s a very nice lady, and obviously, she was very close to W Bush. She was the first woman of color to be Secretary of State. She broke barriers.

I said, “Do you know the picture of W that I took?”

She said, “Yeah, we know it well.”

I told her about my experience with him. How he was very combative, yet smiled in every picture.

I said, “That was a mask, right?”

She said, “No, that wasn’t a mask. He’s a happy-go-lucky guy. That’s who he really is.”

So the real answer is, I don’t know. It’s a mystery.

The Human Condition is a complete, beautiful, terrifying mystery, and we have little moments where we think we understand. People might say, I reveal something in people’s character. I’m not sure what I reveal. And is it the truth? How can it be the truth? It might be a true moment. It might be fake. I was there, and I did engage with these people, and they did give me something, and there must be something true in it, because people seem to connect with the pictures afterwards. But it’s a mystery, and it’s a mystical, weird process. It’s not intellectual. It’s completely emotional, and even when I do it, I take those pictures, and I don’t really understand it myself.

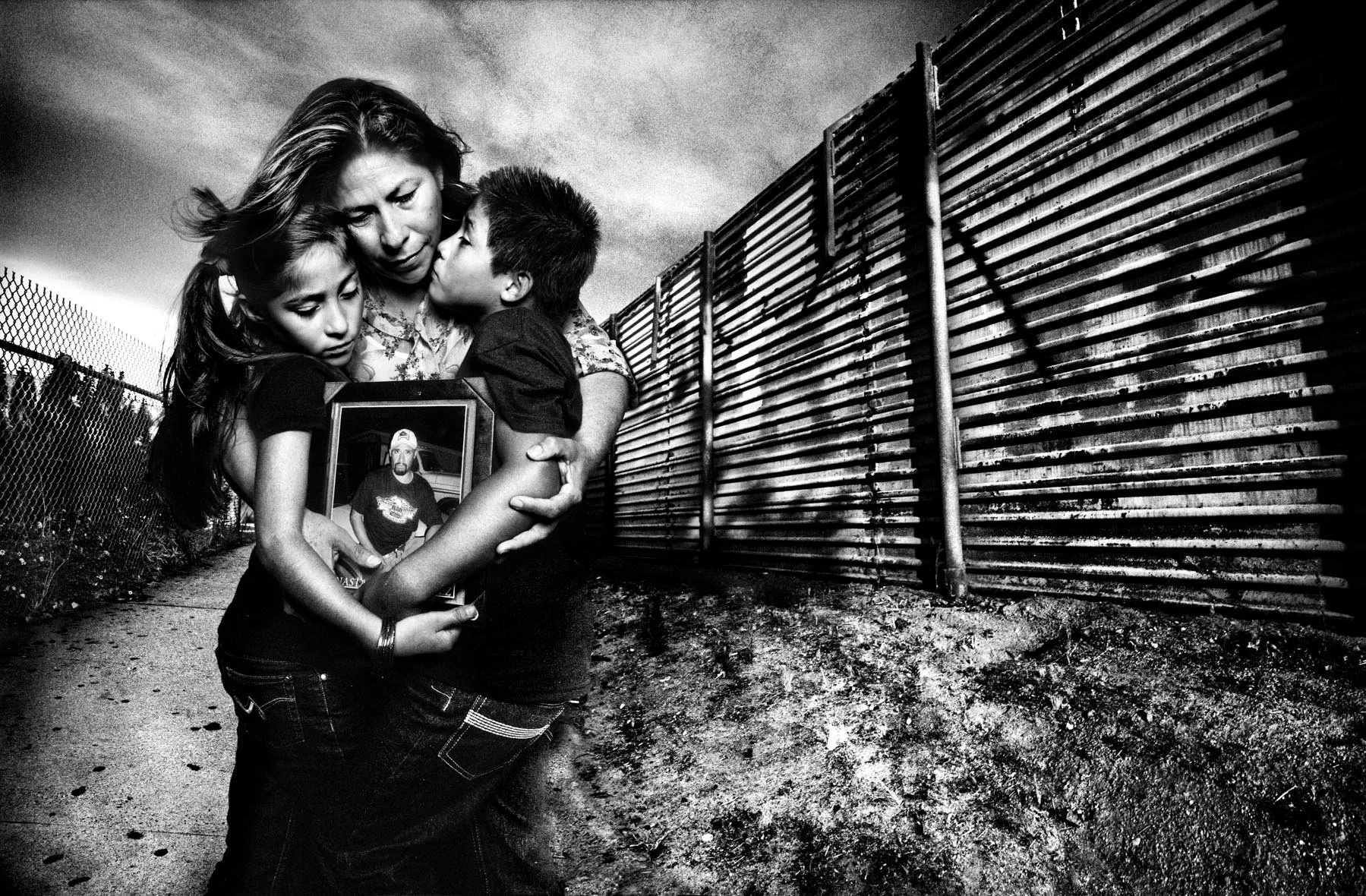

In The Defenders, is your work portraiture, activism, or a form of bearing moral witness, particularly in documenting the Mexico border crossings?

Well, the interesting thing is that these pictures were taken during the Obama era. We automatically assume this is Trumpism, with the aggressive look at immigration and the moral crisis under Obama. Because we were all seduced by the Obama dream, we stopped asking what was really happening.

There was a crisis at the border. So many people were dying trying to cross it. Before Obama, W. [Bush] had militarized the border. But you can’t block the whole border because it goes through the Solomon desert. So, he left the most dangerous parts [open], thinking no one would cross them, and policed the easier sections.

But what [leaders] always underestimate is people’s will to cross the border and have a better life. So suddenly, all those people were now funneling through the most dangerous parts in groups of fifteen or thirty. They were often ill-prepared, and it’s 115 degrees in the heat of summer…so many people die of heat exhaustion alone, women and children, not just men.

I decided we needed to talk about this during the Obama administration, so I spent a year with Human Rights Watch going back and forth across the border. I went to halfway houses, photographing families who had just been deported back over to the Mexican side, and they were all shell-shocked. They didn’t know what to do.

I stood in a morgue surrounded by 300 bodies of women and children who had all died. Things I could never forget and should never forget.

No one wanted to talk about it in the media until Trump came in. I had to beg Time Magazine to run the story online, and it took me a year to get them to run it because it was inconvenient to talk about. It didn’t fit with the narrative that America is suddenly “great again.”

Of course, if you don’t talk about it, the crisis grows. Soon, someone is going to come along and harness the crisis and politicize it, and they’re going to benefit from the crisis, and that’s exactly what happened with Trump. It’s a great fault of the media, I believe, that they didn’t ask enough questions of the people they clearly supported in politics.

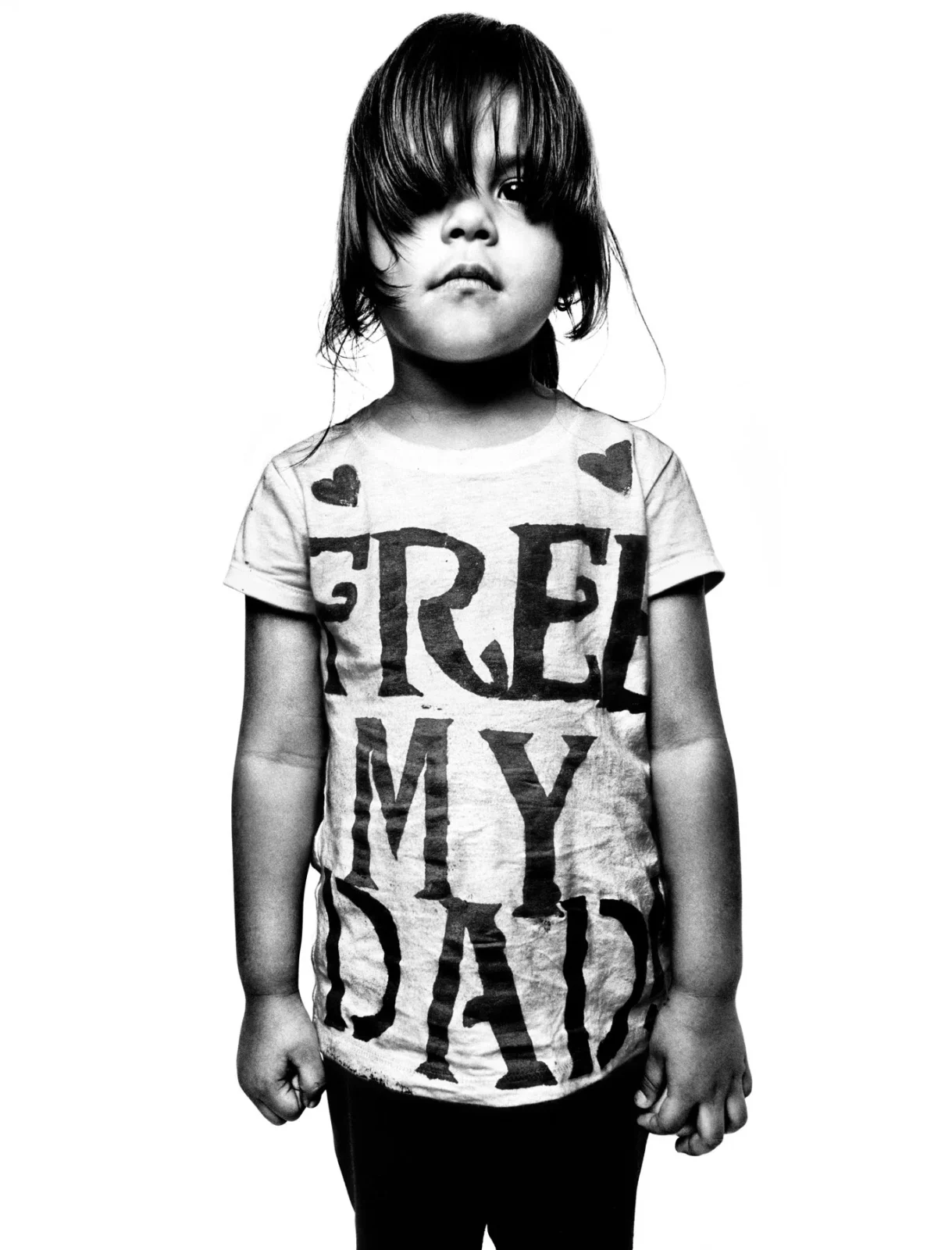

I went to a pro-immigration march supporting human rights. It was in Arizona. There was a street parade, and it was made up mainly of women and children. Mothers with their kids holding up signs saying, “We’re all human together”, things like that. I built a little photo studio on the side of the march and was grabbing people to take their pictures.

I saw this little girl marching with her mother. She was three, and she was wearing this ‘Free My Dad’ T-shirt. It was a hand-painted, homemade T-shirt. The little girl’s name was Evelyn, and she was marching with the incredible defiance that kids have; it’s their world, the future is theirs. She was playful and singing songs. She didn’t really understand what everyone was talking about.

It turns out, her dad had been caught without proper papers and put in a detention centre. Evelyn was a citizen. Her mother was a citizen. Her father was not. So, this policy, going through Obama’s era, was tearing up a family. I thought it was interesting, especially with her T-shirt. I went up to her mom.

I said, “Can I take a picture of your little girl?”

Her mom said, “Sure.”

I said, “Will you come over there where I’ve set up my backdrop?”

She said, “Yes.”

They all walked over. The little girl saw my cameras, my assistants, and members of Human Rights Watch, and she got spooked. She did what all kids would do. She hid behind her mom’s legs.

Now that’s not the picture I wanted to take. I didn’t want a picture of a frightened little girl, because that perpetuates the same narrative that we see again and again in the press. I wanted a beautiful, happy child exercising her freedom in life. I thought that would be a much better story to tell.

To earn the little girl’s trust, I had to play with her for five hours. I never had to earn trust like that with any world leader. I never had to play with balloons with anyone or talk to anyone for five bloody hours. But little Evelyn made me work. After the time was up, she pointed to me and she said, “Picture.” She was ready, so I took her picture, and that’s why the picture looks the way it does, because she knows that we’re now on the level together.

Because of that sense of responsibility do you see yourself as a journalist, whose job is to shape, or a historian, whose job is to pay witness to the truth?

Journalists have always told me there’s a set of rules to be objective. There’s nothing objective about my work.

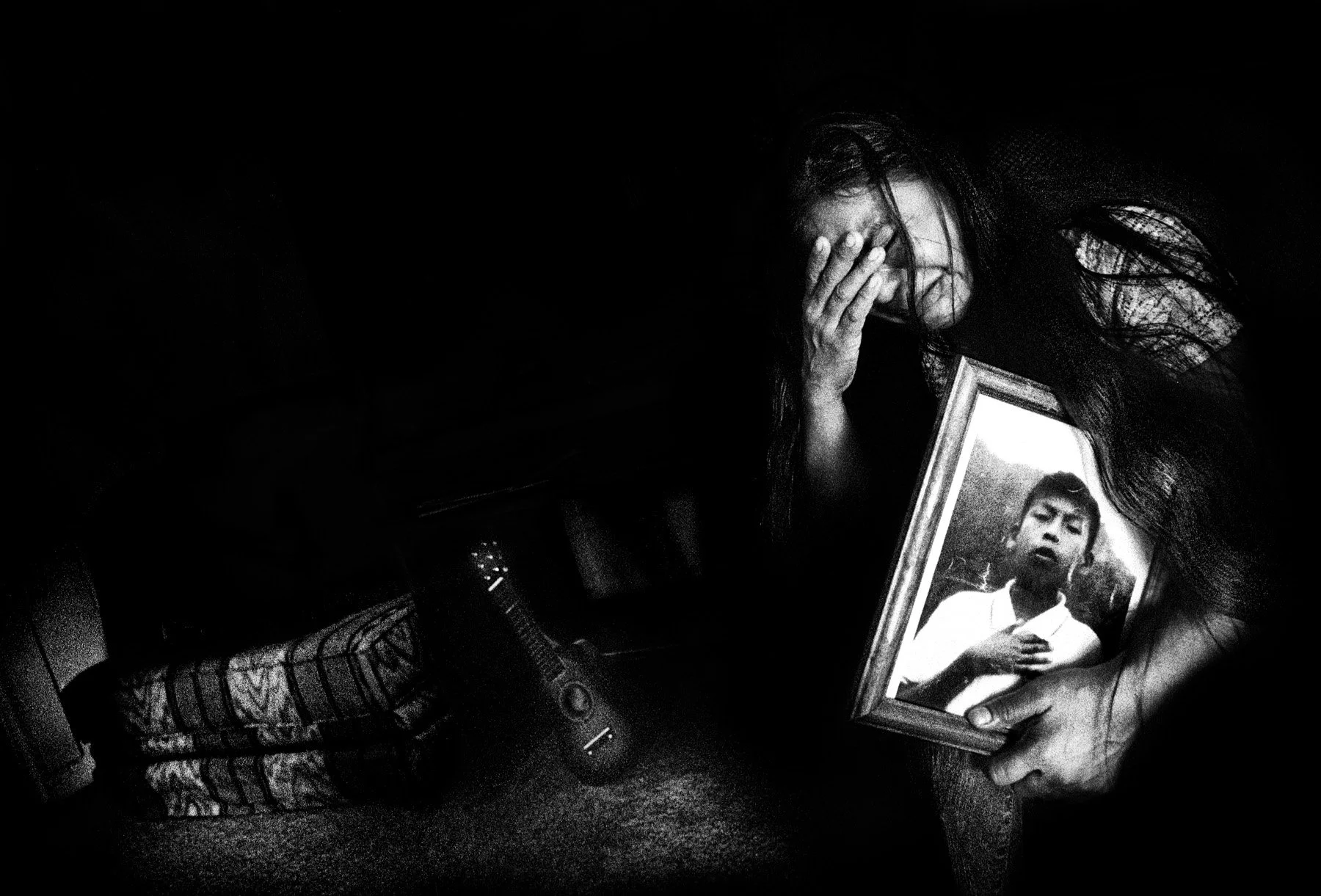

When I covered the border story, I remember hugging a woman who had just found out her son had died crossing the border. He was 10 years old, and he was crossing the border to be with his mum, who had crossed earlier.

She was filled with guilt and pain, and she started to cry as I was taking a picture. And I did what a human being does. I put down the bloody camera and gave her a hug. Now I still remember the vibration of her pain going through my body. She made the sound of a wounded animal.

Journalists have said to me, “Well, you broke the rules. That’s not objective”. But I never agreed to be part of those rules. I’m a human being, and I’m an artist, and I get to do what I want.

For me, this is a collaboration. I’m not observing from a safe distance. I’m working with my subject to amplify their story, and that means I have to earn their trust. I’m asking for a lot, but if they give me their trust, then I will do my side of the bargain. I will deliver their story to as many people as I can. It’s a human story and I’m involved with it.

So, I’m not sure. I don’t think I’m a journalist, and I don’t think I’m a historian, because I live in the present. All my pictures are 1/500th of a second. It doesn’t get more present than that. I think I’m a storyteller, and that means I do it my own way.

I worked with Presidents after that. But how can I look into a President’s eyes now and just see glamor, power, fame, and success? How dare I think that? I see nothing but responsibility—on the President’s shoulders and on mine. If I’m photographing the man who carries so much responsibility, then I’ve also got responsibility on my side.

Now, when I meet a President, it’s like, “Hey, you better get this right.” I know—your fame, your power, that’s all cool. But, man, you are responsible for so many people.

How do you approach photographing powerful figures who understand the power of the image, who know how to use photography as propaganda?

The picture I took of Putin, he loved. Some of his supporters loved it too, using it as propaganda—it shows him as a tough nationalist. But then something interesting happened: his opponents, particularly the human rights community, also embraced it as a banner against abuse of power. In thousands of demonstrations, people carried flags with his face. So much so that the Russian administration issued a decree: anyone circulating that picture in connection with human rights violations would go to jail. The picture is now officially labelled extremist material.

That’s why debate is so important. If I get it right and create an authentic moment with my sitter, everyone will see themselves in that story. My picture of Bill Clinton: his supporters say it’s about charisma—he was a rock and roll president. His critics say it’s about sex and the abuse of women. It’s the same picture. We all see different things depending on who we are. That debate between people—that’s what I want. I don’t want to stop it.

Right now, there’s a big discussion about democracy. Democracy comes from two Greek words: “demos,” the people, and “kratos,” power. What’s happening today is we’ve forgotten what democracy actually means—power to the people—and we think it’s about winning the debate. It’s not. It’s about having the debate. The moment we stop debating what our society should be, someone can harness the situation and just do what they want. I’m all for the debate.

The moment we stop the debate about what our society should be like—if we’re not calibrating all the time and talking about sensitive issues—then someone can harness this situation and just do what they want with it. I’m all for the debate.

If someone hates my picture because they say it makes someone look too good, or someone else loves it because it makes someone look bad—as long as it stimulates the debate, that’s my goal.

I believe in society’s capacity to talk about sensitive issues like Diddy, like Weinstein. These people were once seen as bad boy swagger. Now my pictures represent absolute monsters in society who abuse power. But the really interesting thing is how we celebrated them for so long when we knew the system encouraged and supported it. There’s only one person in prison now dealing with Diddy, and that’s Diddy, and yet he’s being accused of an industry-scale abuse. Industry means a lot of people are in on this. Where are all the others? It’s a system.

This debate about how we’re doing in society is really important. The great irony is that I’m asked to speak about my work all around the world. The whole point of my discussion is to have a respectful debate. Yet, a lot of the time I’m asked to speak, people will say, “We can’t wait for your speech, but it’s a bit sensitive right now. Would you mind taking Netanyahu out?” Or, “Would you just take the Putin one out so we can talk about other things?” Or “Could you remove Diddy?”

I would reply, “Surely, the whole point of asking me to speak is to talk about sensitive issues. And yet you’re asking me not to talk about sensitive issues.” Of course, I have to think, what’s happening in this organization that I don’t know about that is making them ask me to take down this section?

For instance, if it’s Diddy, has someone in their organization been accused of abuse and maybe it’s just too delicate? So, I find it very revealing. Normally, the people who ask you not to talk about something are the ones who are part of it. The people who are not part of it want us to talk about it. Everything is interesting.

Given all of that, what still gives you hope? Why do you keep picking up the camera?

Because I’ve seen people in the worst circumstances. They are really kind and compassionate with each other. We have a privileged life, and we’re all in danger of becoming bitter and cynical. It’s all a question of comparison and perspective.

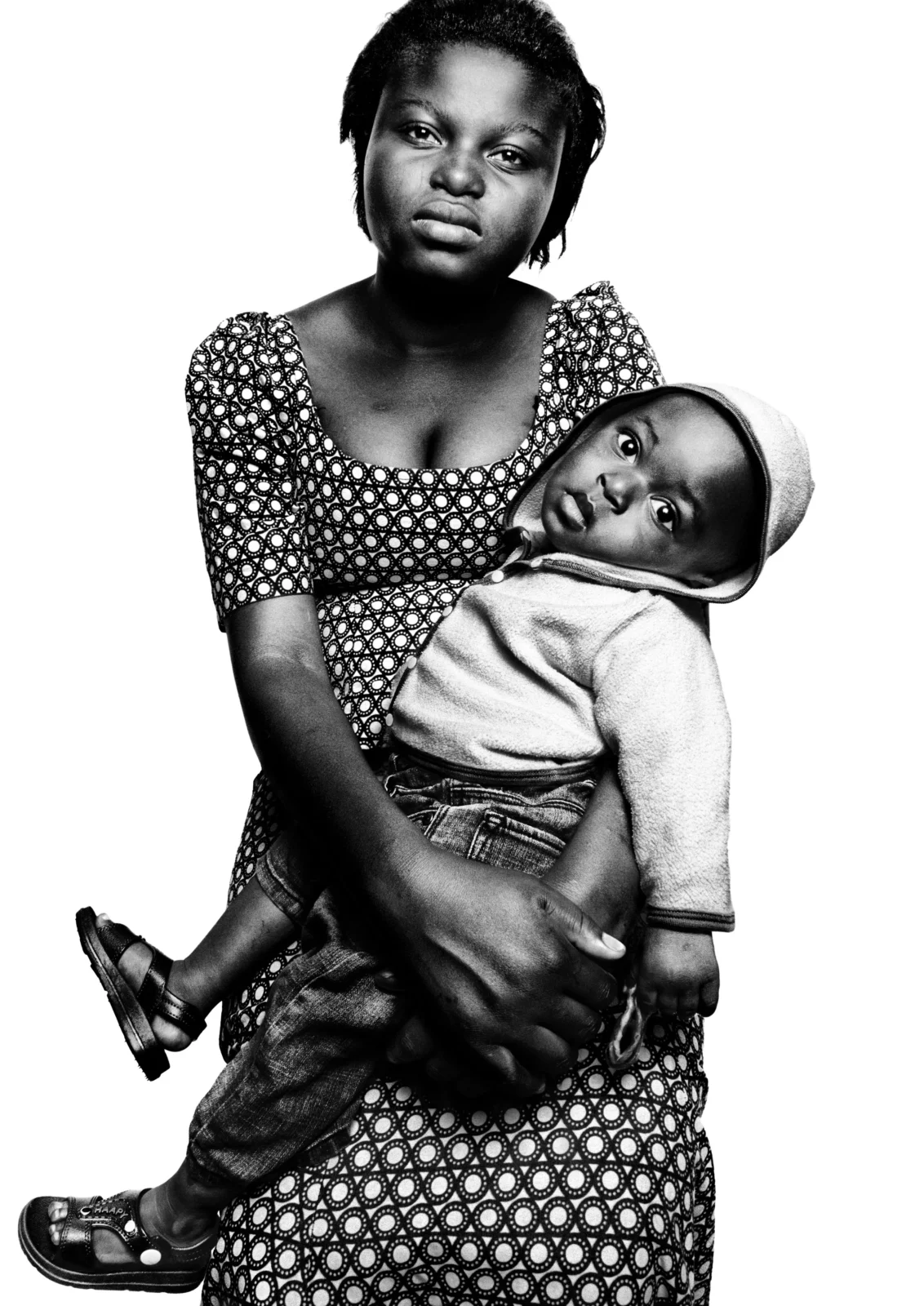

I photographed a 16-year-old girl named Esther. She’s from the Congo, and I photographed her in a hospital. She had a baby on her lap—a beautiful, little baby boy called Josue.

And I said, “Would you mind telling me your story?”

She said, “When I was fourteen, I was fetching water for my parents in a rural area. A gang of militia gangsters took me, captured me, kidnapped me, and took me to their base camp in the forest. She said they tied me to a tree, and forty men raped me for four days. Then, the ropes came undone, and I escaped. I went to a village. A man rescued me from the streets and took me to his home to rest, and then he raped me.”

Eventually, he discarded her because he was finished with her, and she walked for days to get to this hospital because she had heard that there was a doctor there who heals women and children who are survivors of sexual violence.

She was operated on. Her injuries were quite severe, but they fixed her body up, and then they found that she was pregnant from the rape. Then I looked down at her baby, and I realized her baby was born from rape. I have a daughter, and my daughter was the same age as this girl. I started crying. I’d never heard of a story so tragic.

I go to take a picture, and she’s not crying. She has this radiant, compassionate look on her face. It is dignity personified. And I put down the camera, and I said, “With great respect, I’m a middle-aged man who lives in a privileged world. I’m a mess with emotions, and I look at you, and you are not even crying. How can you tell me the story, and I don’t see the same emotion in you that I’m feeling?”

She said, “The reason I don’t cry in your picture is because I don’t want to make you feel sad. I don’t want anyone to feel sad when they look at a picture of me.”

She said, “My mommy and daddy told me that I was put on this earth to bring joy to the world, and I will keep my promise.”

Now, that is a proper leader. She’s been through hell, and she will continue through hell. She has a very uncertain future, and she cares about me, she cares about you, and all the strangers who are going to look at that picture of her. She wants to radiate a moment of optimism.

That’s what optimism is. You find out when you go to the world’s darkest corners. You see the truest of hearts.

I see more cynicism in the privileged side of life than I do in the dark side of life. I feel very privileged to have told these people’s stories. Esther was right to radiate confidence, compassion, power, and leadership. Because that goes through me, and it goes through you. And then if someone reads your story, and is feeling a little lost that day, it will go to them.